Berlin, George Jacques Decker, 1772.

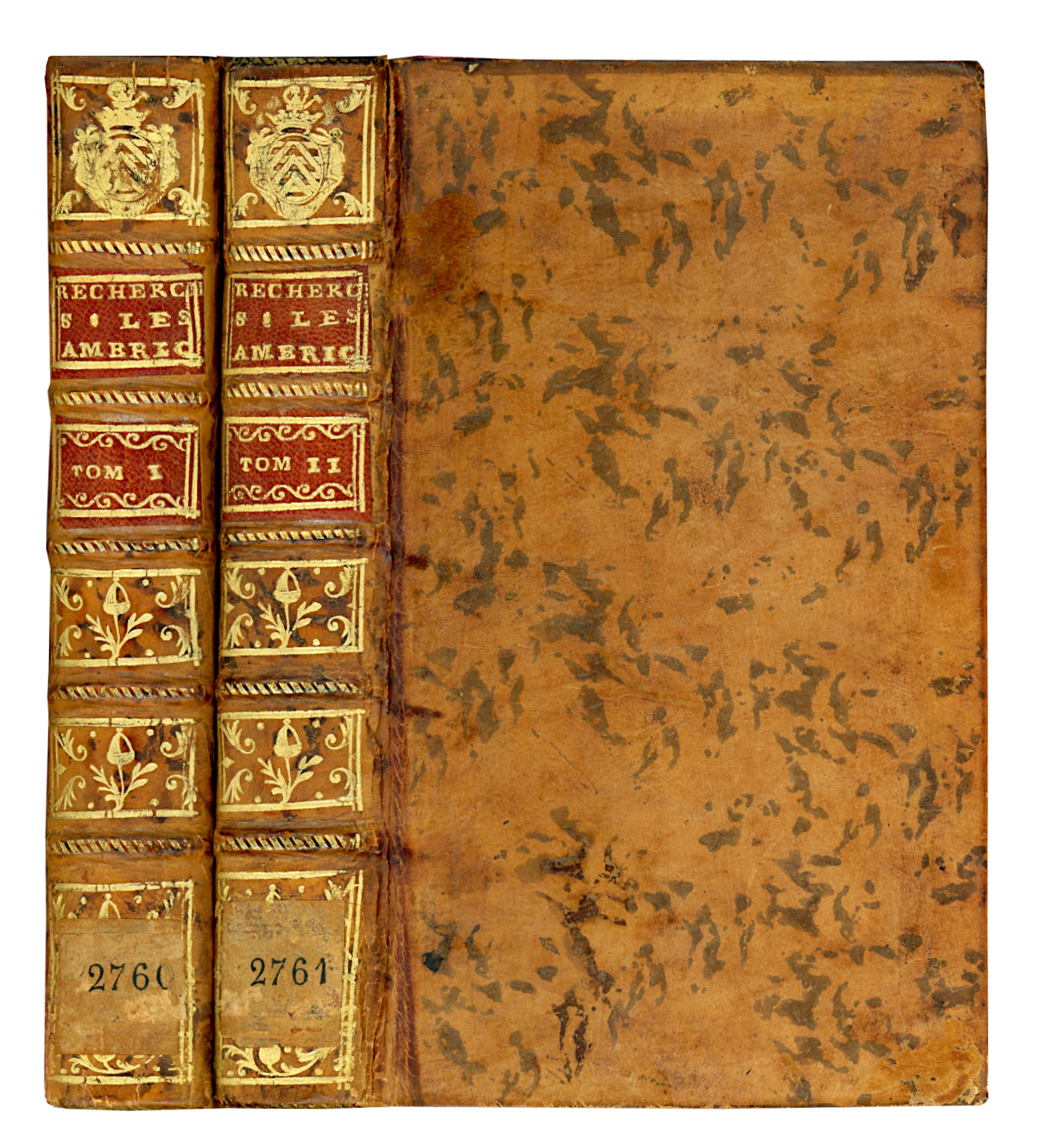

Two 12mo volumes of: I/ xxii pp, (1) l., 384 pp, (15) ll; II/ (1) l., 416 pp, (16) ll, small paper loss on the first 2 ll. of the 2nd volume, filled in on the title. Full marbled light-brown calf, richly decorated ribbed spines with gilt-stamped coat of arms at head, library label at the tail, marbled edges. Contemporary armorial binding.

157 x 96 mm.

The work first appeared in 1768, arousing considerable controversy.

Leclerc, 441 (for the 1774 edition).

Cornélius de Pauw (1739-1799), a Dutch philosopher, stirred up considerable controversy with his various Recherches philosophiques. In his work, an essay in comparative ethnology, he argues that all living species in America are degenerate, hence the controversy with Dom Pernetty, who believed in the existence of real giants.

Carlos Quesada sums up the ambiguity and contradictions of Cornelius de Pauw’s thesis when he writes that “on the one hand, he claims to be an anthropologist and historian, but on the other, he systematically seeks to establish the absolute superiority of European civilization over wild life”.

Diderot and d’Alembert held Pauw and his book in high esteem, and invited him to assist them in the Supplément de l’Encyclopédie, which he enriched with several articles.

The work is also famous for its charge against travel writers.

“We can establish as a general rule that, out of a hundred travelers, sixty lie without interest, & as if out of imbecility; thirty lie out of interest, or if you like out of malice; & finally ten tell the truth, & are men… In this unwelcome crowd of travelers who meddle with writing, there are so few who deserve to be read; but this is not surprising, when one reflects that they are usually merchants, freebooters, shipowners, adventurers, missionaries, religious who serve as chaplains on ships, sailors, soldiers, or even sailors : natural history, political history, geography, physics, botany, are for most of them like the Southern Lands, which we always hear about & never discover”.

De Pauw was of the opinion (shared by other European scientists of the time) that the native Americans were inferior to the natives of northern and western Europe, and that this inferiority was partly due to the American climate and geography.

Some quotations from his works:

The American [native], strictly speaking, is neither virtuous nor vicious. What does he have to be? The timidity of his soul, the weakness of his intellect, the necessity of providing for his subsistence, the powers of superstition, the influences of the climate, all distance him very far from the possibility of improving himself; but he does not notice this; his happiness is to think nothing; to remain in perfect inaction; to sleep much; to wish for nothing, when his hunger is appeased; and to concern himself only with the means of procuring food when hunger torments him. He would not build a hut, nor allow himself to be forced by the cold and inclemency of the atmosphere, nor would he ever leave that hut, nor would he necessarily evict it. In his understanding, there is no gradation: he remains a child until the last hour of his life. Extremely lazy by nature, he is vengeful out of weakness and atrocious in his vengeance…

Europeans who pass through America degenerate, as do the animals; proof that the climate is unfavorable to the improvement of man or animal. The Creoles, descendants of Europeans and born in America, though educated at the universities of Mexico, Lima and the College of Santa Fe, have never produced a single book. This degradation of humanity must be attributed to the vitiated qualities of the air stagnating in their immense forests, and corrupted by the noxious vapors of stagnant water and uncultivated land…

His work caused enormous controversy in its day, and provoked reactions from America’s leading citizens. An “anti-degeneration” campaign against the claims of de Pauw and his colleagues involved such notables as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

A precious copy with the arms of La Rochefoucauld.

“It is a great skill to know how to hide one’s skill”. (Maximes, 245). The Rochefoucauld family was already one of the oldest and most illustrious in France, when François VI, Duc de la Rochefoucauld, published his famous Maximes in the mid-seventeenth century. But it was through his marriage to Jeanne-Charlotte du Plessis-Liancourt that the family acquired the lands of Liancourt and La Roche-Guyon, in the Angoumois region.

The library was naturally influenced by the literary tastes of François VI and his friends, the most intimate of whom were successively Madame de Chevreuse, duchesse de Longueville, and Madame de La Fayette. His successors augmented the library with works on exploration and travel, with which they were obviously fascinated despite the fact that they were obliged to remain close to the king in the offices of grand veneur or grand-maître de la garde-robe.

Books on French history, the nobility and its orders of chivalry are therefore numerous. The male line died out with Alexandre’s death in 1762.