An°. Dni. M. D. LXXVIIII. Cvm licentia svperiorvm Sanctissimo. D. nô. D. Papa Gregorio XIII dicata Ano Dni. 1579. [Colophon:] Perusia. \ Apud Petrumiacobum Petrutium. 1579.

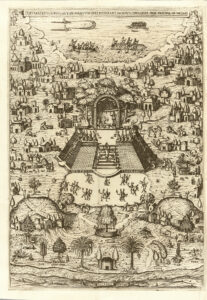

4to of (10) ll. (engraved title, with the arms of Gregory XIII to whom the book is dedicated and the date 1579, dedication, preface, index), 378 pp. including 7 full-page plates, (8) ll., (1) bl.l., 9 plates out of text including 1 folding (placed between pages 168 and 169, depicting the human sacrifice of the ancient Mexicans), each page framed with two fillets, 26 copper-engravings by the author, between pages 298 and 299 a folded table has not been preserved.

Limp vellum, remains of ties, mention Double written in ink on the inside cover, flat spine with handwritten title lengthwise, beginning of title written in ink on the upper edge. Contemporary binding.

242 x 174 mm.

Extremely rare first edition of this precious Americana, which is both a remarkable manual for missionaries in New Spain and a description of the culture of the ancient Mexicans.

Harvard/Mortimer Italian 510; Medina BHA 259; Sabin 98300; Palau 346897 ; Adams V-18; Esteban J. Palomera, Fray Diego Valadés, o.f.m., Evangelizador Humanista de la Nueva España (repr. 1988), passim; Chiappelli and al., First Images of America; Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. Valadés; Leclerc n°1513.

Scarce first edition of one of the most interesting documents for the evangelization of colonial Mexico and the region’s literary and graphic culture, of special interest for its conflation of the Renaissance memory treatise and Native American picture scripts. The son of a conquistador and a Tlaxaca Indian (thus making him one of the first mestizos), Valades is the first Mexican to be published in Europe.

« The Rhetorica Christiana is an extraordinary combination of Old World erudition and New World anthropology (…) His Rhetorica Christiana is almost certainly the first book written by a native of Mexico to be published in Europe (Don Paul Abbott, Rhetoric in the New World, 1996, pp. 41 et suivantes ).

“The most elaborate theoretical attempt to exploit the indigenous mnemonic systems was Diego de Valadés’s Rhetorica christiana, an exhaustive manual on Indian, or more precisely Mexican, culture and on the ways it could be exploited by the missionary in his constant struggle to establish communication with his charges. Most Indian groups, argued Valadés, although ‘rude and uncultured (crassi et inculti)’ had nevertheless contrived a means of conveying messages through ‘arcane modes’, using what he calls ‘figures of the sense of the mind’. These functioned, or so he thought, as the Egyptian hieroglyphs (which until the late eighteenth century were believed to be purely symbolic)” (Anthony Pagden, The fall of natural man, p. 189).

A number of the chapters relate to America and to Native Americans.

This volume bears witness to the direct relations between Rome and the New World.

Very curious illustration drawn and copper-engraved by the author himself, comprising 26 engravings, of which 12 out-of-text, combining figures, mnemonics and information on the customs and habits of the Mexican Indians. Among these is a remarkable folding plate showing a view of Mexico City with a human sacrifice ritual in the center (this plate is upside down in our copy).

The plates afford a rich example of the strange admixture of colonial culture in which the oddly familiar mnemonic alphabets from contemporary editions of Dolce are filled with Indian motifs, or the Crucifixion of Dürer is transplanted to Mexican soil.

Born in 1533 in Tlaxcala, east of Tenochtitlan, to a Conquistador father, Diego de Valadés belonged to the second generation of missionaries in Mexico. A member of the Franciscan order, he spent more than twenty years preaching and listening to the confessions of the Indians. From 1558 to 1562, he took part in a mission to evangelize the Chichimèques, a semi-nomadic people living in the north of the country. After teaching in various Franciscan schools, he was called to Rome, where he served as Procurator General of his monastic order. In 1579, he went to Perugia to supervise the publication of his book, and died a few years later, around 1582.

“The Rhetorica Christiana is a very well-written work, full of interesting notions about the natives of Mexico. The pages he devotes to an examination of their arts and sciences, and what he (P. Valades) says about the variety of their graphic system, prove that he knew them well and appreciated them.” Brasseur de Bourbourg.

Valadès published the important work Rhetorica Christiana in Perugia in 1579, in which he summarized the theological arguments on the nature of the natives and their capacity to learn and practice Christianity. He abounds in the missionary methods of the mendicant orders and the methods they use to evangelize, which is the main focus of several of his engravings, intended to illustrate aspects of this way of preaching, such as engravings 9 and 10, in which he reproduced Ludovico Dolce’s mnemonic alphabet, and the eleventh, in which he presented the one that Spanish missionaries had developed to teach the Latin alphabet to the natives, or 19, entitled Enseignement religieux aux Indiens à travers des images, perhaps the most famous of these, which shows the preacher in the pulpit explaining to a group of natives a series of images with scenes from the Passion of Christ that he points to with a stick or pointer.

Valadès was the son of the conquistador of the same name, Diego de Valadés – originating from Extremadura in Spain, and a member of the Panfilo de Narvaez expedition – and a native woman from Tlaxcala. Educated in Mexiso, he was a disciple and secretary of Fray Pedro de Gante, from whom he learnt the art of engraving and drawing at the school he directed at the convent of San Francisco de México.

“From 1568 onwards, a particular interest in the New World took root in Rome, which struggled to organize itself into structures and networks, but which took advantage of the fundamentally centripetal nature of the city of Rome to reconstitute circles turned towards America, thanks to the particular activity in Rome of a visitor with American experience, as was the case before Valadés for Alonso Maldonado de Buendia, a Franciscan, and after Valadés for José de Acosta, a Jesuit. It was therefore possible for the Holy See to obtain direct information on the New World through a series of characters, a typology of whom is described below. This Roman interest in the New World was a prelude to direct diplomatic action, always thwarted by Philip II, as demonstrated by the long affair of the Apostolic Nunciature of Mexico, finally aborted and replaced first by the entry of American dioceses into the cycle of Ad Limina visits in 1594, and then by the creation of the Congregation De Propaganda Fide. This curiosity therefore had a political and institutional translation, beyond the mere cultural history of relations between Europe and America, especially as the cardinals themselves placed these questions in a global historical perspective by linking money from the Americas with the Flanders War, and extending their horizons to the Asia of the East Indies, where the Iberians were also present.

As for the reconstruction of Diego Valadés’ entire career path, from his birth in Tlaxcala to his as yet undetermined death (in Rome or Antwerp, but certainly not in New Spain), while it first allowed us to visit and enliven the Americanist circles in Rome, it also sought to advance the history of mobility within the Iberian worlds. After all, Valadés had just arrived in Seville from Mexico City, and rushed to Paris in 1572; once in Rome, in 1575, he seemed to have no intention of leaving, since even when expelled in 1577, he took up the anti-Protestant controversy in response to a commission from Cardinal Sirleto, who protected him” (Boris Jeanne).

« The plates and illustrations were drawn and engraved by the author. Some of them represent in their backgrounds Mexican scenes with which the artist was familiar. That there were two or more issues is shown by the plates. The NYP. copy has 8 plates on 7 leaves. In the H. and JCB. copies the plate with the heading “Hierarchia Ecclesiastica” has on its verso another symbolical engraving with the word “Meritorum” inscribed in one of the blank spaces. In the NYP. copy the verso is blank.

The allegorical engraving, which in the list of plates on the last printed page is called “figura Matrimonij & Mechorum,” in the JCB.copy is on the verso of the leaf, and in the H. copy on the recto, both copies having on the back another symbolical engraving with a scroll at the top and the inscription “EGo sum Alpha et 0 ” The recto of the “fIgura Matrimonij & Mechorum” in the NYP. copy is blank. The leaf, which together with this forms a signature, in the H. and JCB. copies is another plate, with inscription beginning “Vulnificum fuso …,” while in the NYP. copy it is blank.

Medina’s Bib. hisp. amer., no. 259, describes two variant issues of the folded table. In one there is a vignette in the lower left corner. In the other there is the following imprint in this corner: Perusia, Apud Petrumiacobum Petrutium, MDLXXIX Permiss Superiorum F. Duidaco Valades. Fratrum Minorum regularis observantia Auctore. The H, JCB, and NYP copies have the vignette.

For a list of chapters relating to America and the American Indians, see Medina.

Graesse’s « Trésor de livres rares et précieux », volume 6, 1867, p. 235, notes a second edition with additions, printed in 1583. Appleton mentions a Rome, 1587, edition » Sabin, vol 26, page 201.

A precious copy preserved in its contemporary limp vellum binding, with the title handwritten in ink on the upper edge and on the spine lengthwise.

It bears the handwritten inscription Ex libris Oratorii Dei Jesu Domus Avenion at the beginning of the volume.

![Rhetorica Christiana ad concionandi, et orandi vsvm acj commodata, vtrivsq[ue] facvltatis exemplis svo loco insertis ; qvae qvidem, ex Indorvm maxime de prompta svnt historiis. Vnde praeter doctrinam, svmâ qvo qve delectatio comparabitur. Avctore Rdo. admodvm P. F. Didaco Valades totivs ordinis fratrvm minorvm | regvlaris observantiae olï procvratore generali in Romana Curia.](https://www.camillesourget.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/004B-V5-CUT-scaled.jpg)

![Rhetorica Christiana ad concionandi, et orandi vsvm acj commodata, vtrivsq[ue] facvltatis exemplis svo loco insertis ; qvae qvidem, ex Indorvm maxime de prompta svnt historiis. Vnde praeter doctrinam, svmâ qvo qve delectatio comparabitur. Avctore Rdo. admodvm P. F. Didaco Valades totivs ordinis fratrvm minorvm | regvlaris observantiae olï procvratore generali in Romana Curia. - Image 2](https://www.camillesourget.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/004A-V5-CUT-scaled.jpg)

![Rhetorica Christiana ad concionandi, et orandi vsvm acj commodata, vtrivsq[ue] facvltatis exemplis svo loco insertis ; qvae qvidem, ex Indorvm maxime de prompta svnt historiis. Vnde praeter doctrinam, svmâ qvo qve delectatio comparabitur. Avctore Rdo. admodvm P. F. Didaco Valades totivs ordinis fratrvm minorvm | regvlaris observantiae olï procvratore generali in Romana Curia. - Image 3](https://www.camillesourget.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/004C-V5-CUT-scaled.jpg)

![Rhetorica Christiana ad concionandi, et orandi vsvm acj commodata, vtrivsq[ue] facvltatis exemplis svo loco insertis ; qvae qvidem, ex Indorvm maxime de prompta svnt historiis. Vnde praeter doctrinam, svmâ qvo qve delectatio comparabitur. Avctore Rdo. admodvm P. F. Didaco Valades totivs ordinis fratrvm minorvm | regvlaris observantiae olï procvratore generali in Romana Curia. - Image 4](https://www.camillesourget.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/DSC_3939-scaled.jpg)

![Rhetorica Christiana ad concionandi, et orandi vsvm acj commodata, vtrivsq[ue] facvltatis exemplis svo loco insertis ; qvae qvidem, ex Indorvm maxime de prompta svnt historiis. Vnde praeter doctrinam, svmâ qvo qve delectatio comparabitur. Avctore Rdo. admodvm P. F. Didaco Valades totivs ordinis fratrvm minorvm | regvlaris observantiae olï procvratore generali in Romana Curia. - Image 5](https://www.camillesourget.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/DSC_3942-scaled.jpg)

![Rhetorica Christiana ad concionandi, et orandi vsvm acj commodata, vtrivsq[ue] facvltatis exemplis svo loco insertis ; qvae qvidem, ex Indorvm maxime de prompta svnt historiis. Vnde praeter doctrinam, svmâ qvo qve delectatio comparabitur. Avctore Rdo. admodvm P. F. Didaco Valades totivs ordinis fratrvm minorvm | regvlaris observantiae olï procvratore generali in Romana Curia. - Image 6](https://www.camillesourget.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Titre-scaled.jpg)