Original edition of the “Collection of heads drawn by Leonardo da Vinci” belonging to the edition with the 60th engraving enhanced with wash, preserved in its unrestored contemporary binding.

References: Louvre, 2003, Leonardo da Vinci, drawings and manuscripts, no. 74.

Paris, 1730.

Leonardo da Vinci. Caylus, Count of. Collection of Heads of character & caricatures drawn by Leonardo da Vinci Florentine & engraved by M. the C. de C.

Paris, at Mariette, 1730.

In-4. Engraved title after Agostino Carracci and enhanced with sepia wash, and 32 plates presenting one to two character heads etched by Caylus after Leonardo da Vinci et Lodovico Cigoli, , totaling 60 heads, printed in bistre, the last enhanced with sepia wash. Followed by 22 pages and 1 leaf.

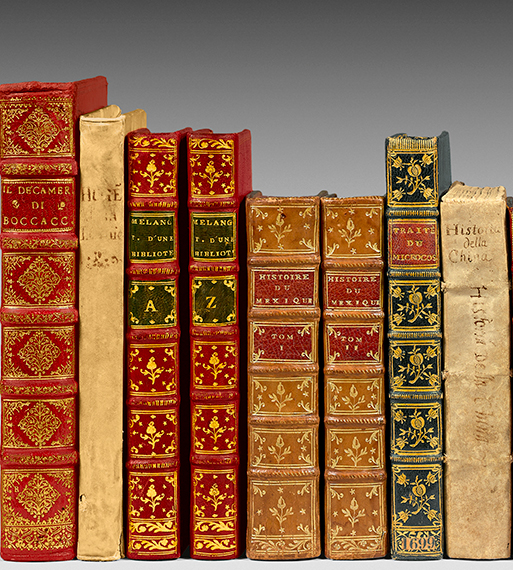

Full marbled calf of the time, ribbed spine with floral motifs, burgundy title piece, roulette on the cuts, speckled edges. Contemporary binding.

287 x 216 mm.

Original edition of the Caylus Album, comprising 60 expression heads (57 in circular medallions and 3 in square or rectangular frames) signed “C[aylus]”. Each figure is numbered, except the last one which has the legend ” di mano di Lodovico Cigoli ».

The count engraved these figures based on Pierre-Jean Mariette’s drawing collection, unless otherwise mentioned: piece 55 is from the king’s cabinet and figures 56 to 59 are from Crozat’s cabinet. The plates are followed by the Letter on Leonardo da Vinci, Florentine painter, to Mr. C. de C., by Mariette, then by two pages of the Catalogue of pieces that were engraved after the paintings or drawings of Leonardo da Vinci.

In 1730, in Paris, at “Aux Colonnes d’Hercule”, appeared the Collection of Heads of character and caricatures drawn by Leonardo da Vinci Florentine and engraved by Mr. C. de C., that is, Count Anne-Claude de Caylus. The publication gathers engravings reproducing grotesque faces then attributed to Leonardo da Vinci. These images are followed by a Letter on Leonardo da Vinci, Florentine painter, to Mr. C. de C., a text of about twenty pages that Pierre-Jean Mariette signs “your very humble and obedient Servant M***”. Attached to this introduction is a brief but precious Catalogue of the pieces that were engravings after Leonardo da Vinci’s paintings or drawings. In this writing, Mariette aims to describe Leonardo’s “manner”, considerations that the reader can test a few pages later by examining the images produced by Caylus. To do so, the expert calls upon categories now recurring in so-called artistic literature. The question of imitating nature and that of representing human passions are thus scrutinized through criticism. A similar approach intends to define the catalogue of the (rare) engravings that reproduce Leonardo’s compositions: Mariette aims to distinguish what belongs to the manner of the Florentine master from that – which he often considers unskillful – of engravers who attempted to translate the master’s inventions. Here, moving from theory to practical exercise, the expert relies little on the categories he had previously invoked: he rather insists on technical considerations, such as the places of conservation of the interpreted works, and advances a few remarks only on the manner in which the transitions between light and shadows are treated.

The “Thead of character and caricatures” are thus commented by Mariette:

Les physiognomies peculiar being what contributes the most to characterizing the passions, Leonard wasequally attentive to making an exact search for it. When he discovered one of them to his taste, if he saw some bizarre head, he seizedit eagerly; he would have followed his object all day, rather than miss it. In imitating them, he entered into the detail of the smallest parts; he made portraits that had a striking air of resemblance. Sometimes he exaggerated them in parts where the ridiculous was more sensible, less as a game than to imprint them in his memory with inalterable characters. The equally attentive to making an exact search for it. When he Carracci and since them several other painters practiced making caricatures except for simple amusement. Leonardo, whoseviews were much nobler, had as an object the study of passions. Thus, for Mariette, a good reader of Vasari, who already interpreted the “bizarre heads” in this light, Leonardo reproduced faces by “exaggerating” certain features, not for play (or mockery) but to imprint them in his memory. The Collection – which Mariette and Caylus intended for their “friends” – includes sixty “bizarre heads”, all etched by the count of Caylus (except for no. 54 executed by Charles-Antoine Coypel). The faces, of men and women, presented against a slightly shaded neutral background, are oriented some to the right, others to the left. They are presented individually, not in pairs, as in other engraved translations of these subjects, for example in those by Hans Liefrinck (circa 1550-1560) or Wenceslaus Hollar (circa 1645). For the most part, the count of Caylus’s faces are integrated into a medallion. They are accompanied by no commentary, only a number and the initial C, for Caylus, punctuating the circular frame. beaucoup plus nobles, avoit pour objet l’etude des passions.

Ainsi, pour Mariette, bon lecteur de Vasari, qui, déjà, interprétait les « teste bizzarre » sous cet angle, Léonard reproduit des visages en « chargeant » certains traits, non par jeu (ou par moquerie) mais pour les imprimer dans sa mémoire.

The transcription aims to best capture the “ductus” of the master; the ambition is to follow the artist’s stroke to better convey his art through the print. Moreover, the count of Caylus’s models are known: the engraver translates an album of pen drawings, brown ink and gray wash (respecting their dimensions), today preserved in the Louvre (inv. RF28725 to RF28785). It was Mariette’s father who acquired this volume from a Parisian merchant, after 1719. This is known from Mariette himself, who writes in his introductory remarks: ”

La transcription tend à capturer au mieux le « ductus » du maître ; l’ambition est de suivre le trait de l’artiste afin de mieux faire connaître son art à travers l’estampe. D’ailleurs, les modèles du comte de Caylus sont connus : le graveur traduit un album de dessins à la plume, encre brune et lavis gris (en respectant leurs dimensions), aujourd’hui conservé au Louvre (inv. RF28725 à RF28785). C’est le père de Mariette qui avait acquis ce volume auprès d’un marchand parisien, après 1719. On le sait par Mariette lui-même, qui l’écrit dans ses remarques introductives : « Herein lies the Collection of Heads which has just joined my father’s Cabinet “. This is also known from an annotation left by Antoni Rutgers (1695-1778), art lover and dealer in Amsterdam, on one of the examples of the Caylus and Mariette publication today preserved in Leiden (University Libraries, Special Collections, Art History 21219 B 14 KUNSTG RB: I B1429). According to Rutgers, the drawings acquired by Mariette father had belonged to Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, then to Sir Peter Lely, court painter in England, then again to Van Bergesteyn and Siewert Van der Schelling, Dutch collectors. Put on sale in Amsterdam in 1719, they were bought by Parisian merchant Salomon Gautier for 370 florins (about 740 livres), then by Mariette father for 1,000 livres. In his Letter on Leonardo da Vinci, Pierre-Jean Mariette also supposed that the drawings bought by his father had passed through the prestigious collection of the Earl of Arundel (thereby enhancing their prestige). His reasoning is reminiscent of the approach used by researchers when studying today the faces grotesque by Leonardo:

The Collection of Heads Drawings I’ve mentioned may have belonged to this illustrious Collector [Arundel]. I base my conjecture on the fact that several of these Heads were previously engraved by Wenceslaus Hollar. You are not unaware that this Artist was in the service of the Earl of Arundel, and that the rich Cabinet of this Lord provided him with the greatest part of the Masters’ Drawings he engraved. He seems to have particularly focused on those of Leonardo, no doubt to honor himself with such a great name. In fact, the number of Plates he engraved after this Painter amounts to nearly a hundred, composing several series. These Plates are executed like everything Hollar did, with infinite cleanliness; one might only desire more taste, and that the manner of the Author was a little less disguised therein. However, because these Prints are after Leonardo, they are still highly sought after by Collectors today.

Be that as it may, at the death of Pierre-Jean Mariette in 1775, the drawings that had served as models for Caylus lose their status as originals: recorded at the Mariette sale under no. 787, the album is bought for only 240 livres. It is now known that this album gathers copies of drawings by Leonardo, today preserved in the Devonshire collection at Chatsworth, sheets that indeed probably belonged to the Earl of Arundel. As Pascal Griener, Cecilia Hurley, and Valérie Kobi have already pointed out, there is something paradoxical – or even comical – about this epilogue: for Mariette and Caylus, the attentive contemplation of past models and the faithful reproduction of artworks recognized as original allows familiarity with the art of the ancient masters, an intimacy that permits relevant considerations, the famous “discourse founded in judgment”. Yet it’s based on copies, perhaps even made by a northern artist (the drawings of the Mariette Album are today attributed to Constantijn Huygens the Younger), that the two experts constructed their discourse on Leonardo’s work!”

References: Louvre 2003, Leonardo da Vinci, drawings and manuscripts, no. 74; Cohen 623.

Precious copy in unrestored contemporary binding belonging to the edition with plate 60 in wash.