The very same copy described by OlivierHermal bound at the time by Rocolet

from the libraries Charles de L’Aubespine (1580-1653),

Lang (1925, no. 38) and Estelle Doheny with ex-libris.

La Chambre, Cureau de. Treatise on the Knowledge of Animals, where everything that has been said for & against the reasoning of beasts is examined: By Sieur de la Chambre, Physician to Monseigneur the Chancellor.

Paris, at Pierre Rocolet, Royal Printer, 1647.

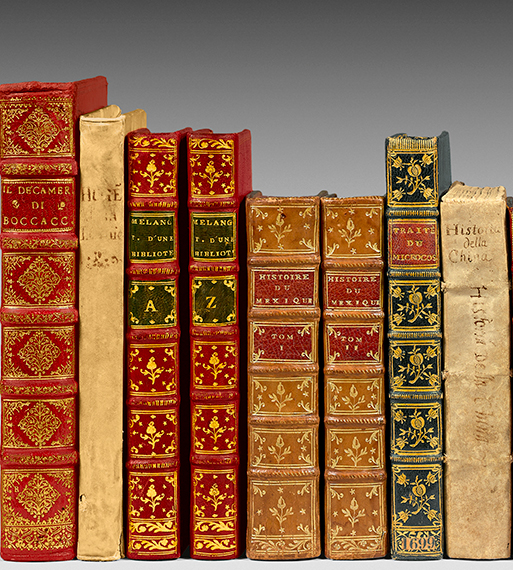

In-4 of (4) ff., 30 pp., (5) ff. of table, 390 pp. Red morocco, boards decorated with various gilt frames, with gilt fleur-de-lis and pointillé corner ornaments, coat of arms in the center, spine with raised bands finely adorned, decorated edges, inner roller, gilt edges over marbling. Binding of the time from thePierre Rocolet – Antoine Padeloup Workshop.

233 x 168 mm.

Original edition dedicated to Chancellor Séguier of this major text on the debate about the soul of animals.

Marin Cureau de La Chambre was born in Le Mans in 1594.

“Cardinal Richelieu chose him, among the brilliant minds of the time, to have him join, in 1635, the newly founded French Academy. He was also one of the first members of the Academy of Sciences in 1666. Louis XIV was so persuaded of this skilled physician’s talent, to judge people’s physiognomy, as to discern not only the basic character but also which positions each might be suited for, that the monarch often made decisions only after consulting this oracle.

His secret correspondence with Louis XIV is mentioned in vol. 4 of the Interesting and Little-Known Pieces, by M. D. L. P. (de la Place); it ends with these words: ” If I die before His Majesty, she risks making many poor choices in the future. ».

“The treatise by Cureau de la Chambre is a key piece in the debate on ‘the soul of beasts’ that extends throughout the entire 18th century, notably with Condillac and Buffon.”

“It is in the sense of a true materialist psychology that Marin Cureau de la Chambre will reread, a few years after the publication of the ‘Discourse on the Method,’ the texts of Montaigne, defending Charron against the attacks of Pierre Chanet. The text of the ‘Treatise on the Knowledge of Animals’ remains seemingly scholastic by its language: understanding is affirmed as dependent on the imagination, which is, in a sense, nothing other than the thesis of Aristotle or Thomas Aquinas; however, for Cureau, this dependency is explained in an entirely different way. According to Aristotle and the scholastic tradition, sensation contains ‘in potential’ the judgment that understanding can exercise based on sensible images: neither sensation nor imagination judge by themselves, and the dianoetic faculty is necessary to form a proposition and reasoning from sensible data, and it alone is the true ‘subject.’ It is this nuance that Cureau de la Chambre’s psychology questions. The issue is whether animals can judge; Cureau, like Montaigne, answers affirmatively, but, as a good disciple at this point of the scholastic tradition, Cureau also asserts that animals live reduced to sensations and images: therefore, sensation and imagination must themselves produce judgment and reasoning; thus, the entire second part of the ‘Treatise on the Knowledge of Animals’ aims to show that the copula ‘is’ can be added between the subject and the predicate by the imagination itself, which thus has the faculty not only to form images but also to unite them. The third part goes further, showing that the imagination is capable of forming – always by itself – syllogistic reasoning, by uniting two propositions to form a third: as a producer of ‘is,’ animal (material) sensation also becomes of ‘therefore.’ What remains for man? The simple faculty of uniting not only singular terms but also general terms…” (Thierry Gontier, From Man to Animal, Montaigne and Descartes or the Paradoxes of Modern Philosophy on the Nature of Animals).

“It is not that the soul has no part in ethical behavior, but the soul is not a principle that would distinctly differentiate human behavior from animal behavior. Indeed, the soul seems fundamentally material in Cureau. Just like Aristotle in ‘De Anima,’ he mentions in his ‘System of the Soul’ (1664) a purely intellectual part of the soul without ever defining its characteristics and actions clearly. The rest of the soul, so to speak, being material, is not unique to humans alone. Cureau’s conception of the soul thus allows further reinforcement of the similarities between animals and humans since these two essential components of the living are endowed with souls.

This thesis of Cureau is known through the debate he had with Pierre Chanet. The latter defends the Cartesian position of an animal-machine, namely without a soul. Cureau instead affirms its presence in animals. Animals are not only on equal footing with humans, but they are ‘more than men’ since they serve as models to understand human beings.

Now, it is the very thesis that animals have a soul that makes the idea of animal morals possible. The existence of a soul in beasts is the original thesis justifying that Cureau’s comparative method extends far beyond the physiological. In the strict sense of the term, there exists indeed animal psychology and the characters linked thereto. The passage through the observation of animal passions to understand those of human beings is for instance clear from the beginning of the first sentence of the ‘Treatise on the Knowledge of Animals’: ‘In the necessity imposed upon us by the Treatise on the Passions of searching for the causes of love and hatred found among animals…’. A rigorous analysis of passions requires going back to the two fundamental opposing feelings guiding animal behavior. The link is both logical and methodological and the association of ideas is immediate: to address human passions, one must start from those of animals and more precisely start from the two poles of all behavior (animal or human): love and hate. One cannot analyze human passions without starting from animal passions.

Cureau uses the plasticity of the Aristotelian concept of the soul to give morals to animals and claims it: ‘I have deviated in no way from the School’s accepted principles, and I did not want to destroy, as is done now, neither the faculties of the soul, the sensible qualities, nor the images of memory, nor the knowledge of animals’.

Whether or not there is an allusion to Descartes here, the important thing is that the author finds imagination, memory, and above all knowledge in animals. By asserting that they have a soul, Cureau proposes a definition of the soul that erases the boundary between the rational and the infra-rational. To do this, he posits imagination as an essential faculty of the psycho-cognitive apparatus of all moving beings. All knowledge being the transport of images, all knowledge is a way of imagining: ‘imagination can form and unite several images, and consequently… it can conceive, judge, and reason’. There is therefore only a difference in degree between human thinking and animal thinking, both being the transport of images within and by the soul…

This blurring of the boundary between human and animal behavior (through the identification of thought with imagination and the rejection of instinct) could have something skeptical about it, recalling, in the manner of a Montaigne, that there is sometimes more difference from man to man than from man to animal. But for Cureau, it is not at all about anti-speciesism with a relativistic aim. Models to think about human passions are indeed sought, so the influence remains apparently always Aristotelian…” (Marine Bedon, Man and Beast in the 17the century. An Animal Ethics in the Classical Age?).

Copy adorned with a sumptuous red morocco binding decorated with the arms of Charles de l’Aubespine (1580-1653).

He became suspect to Richelieu, who had the seals taken from him at Saint-Germain-en-Laye on February 25, 1633, and detained him in Angoulême until May 24, 1643.

“Finally freed, he returned to his house in Montrouge, near Paris, but he had to resign from the position as Chancellor of the Order of the Holy Spirit in March 1645. After a disgrace of more than 17 years, he was recalled to court on March 1,er 1650, and resumed the seals on March 2; he kept them until April 3, 1651, and received the title of minister of State. Again in disgrace, he was exiled to Bourges in November 1652 ».

Fine binding of the period from the workshop Pierre Rocolet – Antoine Padeloup.

“Rocolet’s clientele, that for luxury bindings, was the supreme elite of the time: the Queen, the Cardinal, the Chancellor, also Dr. Marin Cureau de la Chambre, capable physician, ingenious philosopher and prolific writer, strongly protected by the all-powerful Chancellor Séguier. His books were the most richly dressed from the workshop “. Raphaël Esmerian.

The copy is precisely the one described by Olivier Hermal, plate 955.

Provenance: Marquis de l’Aubespine (1580-1653); Lang (1925, no. 38); Estelle Doheny with exlibris.