“Examples of complete sets of any issue or state of Larmessin are unknown:

the B.n.F. houses a suite of 76 plates, the Metropolitan Museum has a suite of 41”.

The most precious copy to have been on the market for half a century

rich with 75 etchings by Larmessin and 682 plates (in total) of characters,

costumes and trades of the reign of Louis XIV.

The only copy in armoried period binding listed for half a century.

Paris, 1680-1696.

Larmessin, Nicolas de. [Paris], s.n., circa 1700. [The Grotesque Costumes and Trades (= Habits des métiers et professions)].

In [collection of fashions from the reign of Louis XIV].

Paris, 1680-1696.

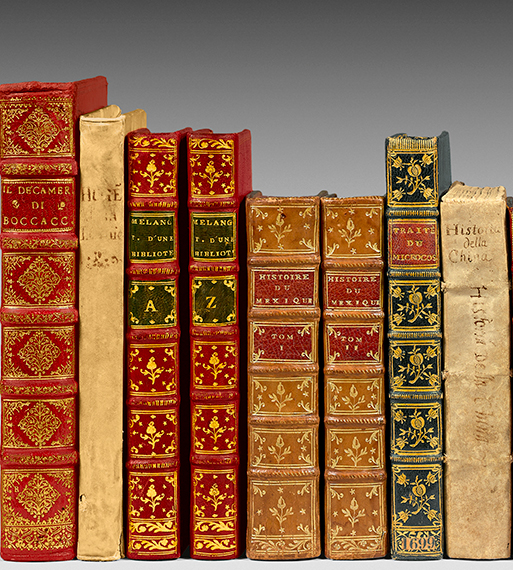

2 folio volumes assembling 682 intaglio and etched plates, of which 7 are colored and heightened with silver. Three prints restored.

Full mottled brown calf, spines with raised bands, gilt title, arms at the center of the boards, decorated edges. Armoried bindings of the period.

375 x 255 mm.

The most complete collection of grotesque costumes and fashions of the reign of Louis XIV with that of the B.N.F (see below).

Exceptional collection created at the end of the 17th century by Louis 1er de la Tour du Pin de la Charce (1655-1714) and bound to his arms.

Godson of Louis XIV, from one of the oldest families in France, Louis 1st de La Tour du Pin was a cavalry captain, knight of Saint Louis, member of the States of Burgundy, and the first gentleman of the Prince of Condé. Among other titles, he bore the titles of Marquis de la Charce, Count of Montmorin and Oulle, and, by his marriage, Marquis of Fontaine-Française and sovereign prince of Chaume, surrounding his coat of arms. (Richard-Edouard Gascon, History of Fontaine-Françoise, Paris, 1892, pp. 314-315).

These two volumes offer a spectacular review of characters, costumes, and trades from the century of Louis XIV. The ‘fashion portraits’ are particularly well represented, engraved by several members of the Bonnart – Henri II, the most famous, his brothers Nicolas I and Robert -, representing the celebrities of the time as attractive young models, starting with the king, Madame de Maintenon, the royal family, the Court.

D’Henri Bonnart also includes several prints from his series of allegories put into fashion.

The other fashion engravings contained in these volumes are by Jean Dieu de Saint-Jean, now regarded as the inventor of the genre, and his Parisian followers Claude-Auguste Berey, Nicolas Arnoult, or Antoine Trouvain. There is also a very important set (75 plates) of ‘grotesque costumes’ by Nicolas de Larmessin, a fascinating series of allegorical portraits composed from the tools and products of their trade.

“Rare suite of 75 folio-size engravings from the printmaker Nicholas II de Larmessin’s (c. 1645-1725) famous series of Grotesque Costumes, first conceived by the artist’s father, Nicholas I, in the 1690s and gradually expanded to include some 100 unique designs issued separately or in various groupings with contents depending on a client’s choice of subjects, a printseller’s pre-selected choix or some combination of the two. Issued without a title page and variously called the Habits des métiers et professions or Grotesque Costumes and Trades, these folio-size prints depict contemporary tradesmen (and women) wearing costumes composed of the tools, instruments, accessories, and wares used in the exercise of their professions. The project represents an ingenious melding of two well-known genres: the fanciful composite portraits painted by Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1526-93) and the popular prints known as “Cries,” in which readily recognizable street hawkers, peddlers, and local types of various reputation were delineated in a purportedly documentary manner. Recent research suggests that Larmessin was likely also influenced by the ballet costumes designed by Henry de Gissey (c. 1621-73) and Jean Berain (1637-1711), which were published by Jacques Lepautre (c. 1653-84) in the early 1680s (Préaud, p. 244).

Here we have, for example, a costume of the printer (Printer en letters) as an unwieldy press fully enclosing the body of the craftsman who skillfully manipulates the letter case, ink ball, tympan, bar, and frisket of his own clothing. The fisherman (Fisherman) is a proud aristocrat with a net for a cape, a crab trap for a scepter, lobsters for greaves, a flounder and perch for a breastplate, and an eel for a belt. Whether more closely related to Ancien Regime stagecraft, to Arcimboldesque capricci, to the exotic costume books of such artists as Jost Amman (1539-91) and Nicolas de Nicolay (1517-83), or to the social realism of such publications as Marcellus Laroon’s (1653-1702) Cryes of the City of London Drawne after the Life (1687), the Grotesque Costumes of Larmessin have long intrigued both casual viewers attuned to the comic charms of these prints and cultural critics in search of a fuller historical context to help explain their eccentricity.

Roland Barthes (1915-80), while aware of the simple pleasures of these works, also sees Larmessin’s project as a “superlative case” of a “vestimentary lexicon” that links clothing “either to anthropological states (sex, age, marital status) or to social ones (bourgeoisie, nobility, peasantry, etc.).” The work is not as lighthearted as it at first seems, but is the product of “a society which was starkly hierarchical, in which fashion was part of a real social ritual.” Barthes recognizes in Larmessin, “a creation which is both poetic and intelligible, in which the profession is represented by its imaginary essence [;] in this fantasy, clothing ends up absorbing Man completely, the worker is anatomically assimilated to the respective instruments and in the end it is an alienation which here is described poetically: Larmessin’s workers are robots before la letter” (Barthes, The Language of Fashion, p. 20).

Because of the fragmentary nature in which Larmessin’s plates have come down to the present day, the publication history of the Larmessin oeuvre is yet to be fully documented. Examples of complete sets of any issue or state of Larmessin are unknown: The B.n.F. houses a suite of 76 plates, the Metropolitan Museum has a suite of 41, and OCLC locates two U.S. Libraries with Larmessin engravings included as part of larger costume sammelbands, (Brown, Clark Art Institute). Lipperheide cites a volume with 38 plates; but even individual engravings are rare both in institutional collections and on the market.

References: Lipperheide, vol. 2, p. 118, no. 1971 lists a suite of 38 prints; R. Colas, General Bibliography of Costume and Fashion , no. 1779;, no. 1779; Inventories du French century, centurye (1973), vol. 6 (Nicolas II de Lermessin), nos. 12-86; IFF XVII (1993), vol. 11, nos. 23-8 (Jacques Lepautre); Maxime Préaud, catalogue entry in P. Fuhring et al., eds., (1973), vol. 6 (Nicolas II de Lermessin), nos. 12-86; IFF XVII (1993), vol. 11, nos. 23-8 (Jacques Lepautre); Maxime Préaud, catalogue entry in P. Fuhring et al., eds., A Kingdom of Images: French Prints in the Age of Louis XIV, 1660-1715, p. 224, no. 86; G. Valck, Fantastic Costumes of Trades and Professions; S. Benni, ed., The Archimboldo dei trades: Visionary fantastic e costumes grotesque in prints; Roland Barthes, The Language of Fashion, A. Stafford, trans., (Oxford: Berg, 2006).

Pascale Cugy, “The Manufacture of the Desirable Body: Parisian Fashion Engraving under the Reign of Louis XIV” History of Art, no. 66, 2010, pp. 83-93.

The most precious, the most complete, and the only copy in armoriated period binding to have been on the market for half a century.