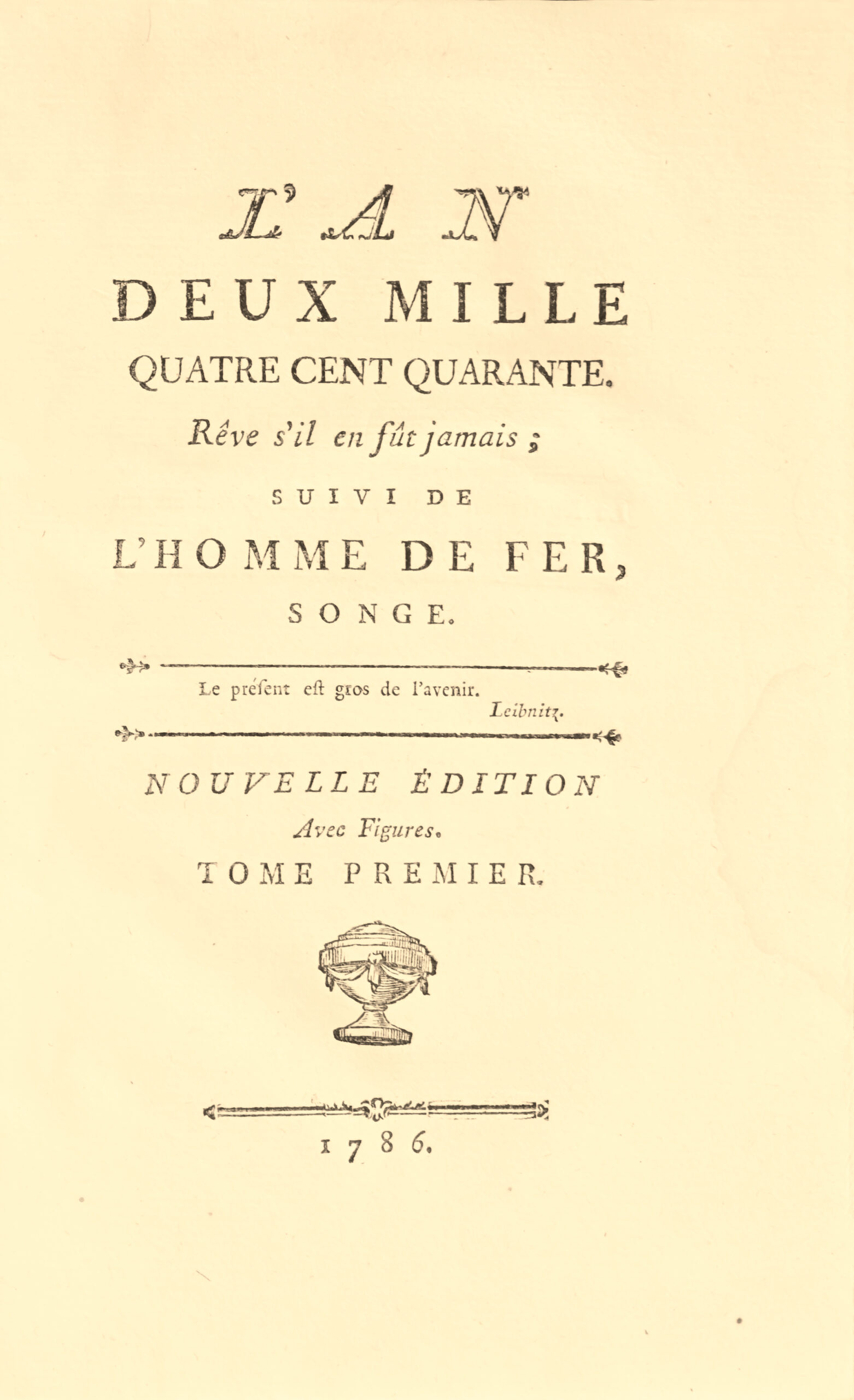

N.p. [Paris], 1786.

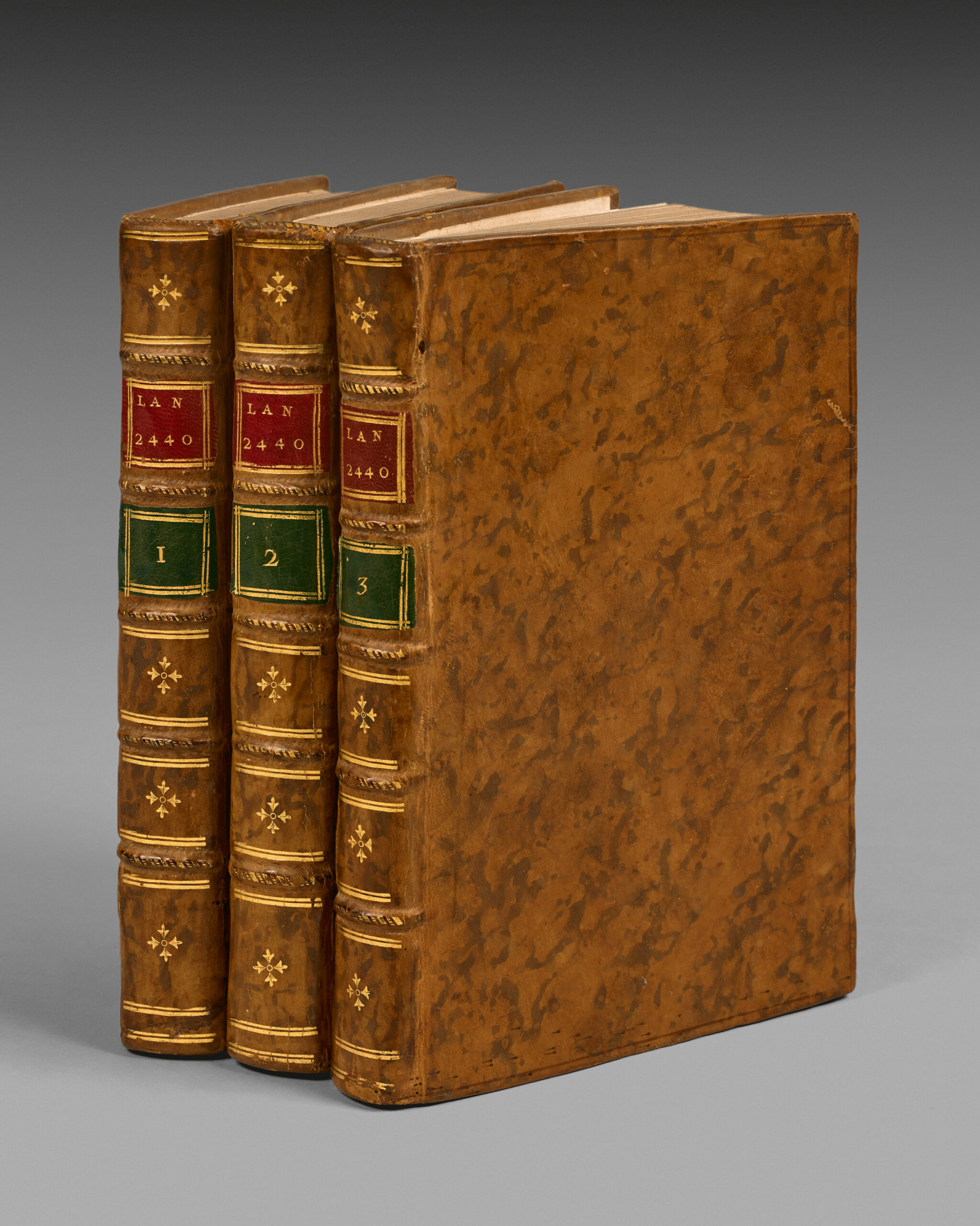

3 volumes 8vo of: I/ xvi pp., 380 pp., (1) l.; II/ (2) ll., 381 pp., (3); III/ (2) ll., 312 pp., (2). Marbled calf, blind-stamped fillet around the covers, spines with raised bands decorated with gilt fleurons, title and volume number labels in red and green morocco, mottled edges, slight loss of leather on 2 covers. Contemporary binding.

189 x 120 mm.

First complete edition, partly original, of the first science fiction novel, the first to comprise three volumes.

This novel was widely pirated between 1771, the year of its first publication, and 1786, when Mercier added a third volume.

This work, a pioneer of science fiction literature, transports the author into the future, into a society where the ideas of the enlightenment are put into practice; it had a considerable impact throughout Europe.

L’An 2440, rêve s’il en fut jamais can be considered the first science fiction novel in which the philosophy of the Enlightenment is reflected. It is the first utopia set in another time, rather than on another Earth. It expresses the contrast between the system of absolutism and a free society, albeit still under the rule of a king, where personal merit has replaced hereditary privileges.

This text, whose structure essentially mirrors the organization used to create the Tableau de Paris for each specific subject in a particular chapter, is, above all, a scathing critique of the flaws of contemporary society. Deeply concerned for the well-being of his fellow citizens, The author uses this science fiction novel as a platform to denounce abuses in the hope that the ruling class will dare to make the changes necessary for human happiness. Mercier criticizes the fact that the king does not care enough about the people. He is preoccupied with the palace, parties, monuments, and splendor, instead of improving the living conditions of the people and enlightening them. The moral: “monuments of pride are fragile.”

After a discussion with an Englishman, who shows him all the flaws of French society in the last third of the Enlightenment (1770, during the reign of Louis XV), the narrator falls asleep and wakes up after sleeping for six hundred and seventy years, in 2440, in the midst of a society that has been renewed many times over in a France that is just as he could have imagined it, liberated by a peaceful and happy revolution. Oppression and abuse have disappeared; reason, enlightenment, and justice reign supreme. The entire novel depicts this renewed Paris and ends with a scene in which the narrator goes to Versailles and finds the castle in ruins, where he meets an old man who is none other than Louis XIV: the old king weeps, consumed by guilt. A snake, lurking in the ruins, bites the narrator, who wakes up.

Several of his prophecies came true during Mercier’s lifetime, and he was later able to say, speaking of the year 2440, even though he did not believe in the success of a political movement before 1789: “It is in this book that I unequivocally revealed a prediction that encompassed all the possible changes from the destruction of the parliaments to the adoption of round hats. I am therefore the true prophet of the revolution, and I say this without pride.”

This text went through three versions (1771, 1786, and 1799), and some of Mercier’s additions (mainly footnotes) show an author satisfied to point out that certain abuses had ceased since the first publication of his alternate history.

On the eve of the Revolution, this work, inspired by the Enlightenment, was a scathing attack on royal power and social inequality. It proposed a fairer government and greater equity in the distribution of wealth.

Mercier thought of his alternate history as a feasible prediction, which is why he boasted of having foretold the French Revolution. Mercier makes the city a social space linking freedom to work and, de facto, pushing it to sacrifice individual freedom for the collective happiness of Paris in 2240, where women are confined to domestic pleasures.

The authorities took the philosopher’s dream to be a pamphlet against the existing social order and the work was banned, which explains why the editions mention London as the place of publication. These are probably fictitious places to escape the destruction of the book. The work, first published in 1771, was a great success and was widely translated into Italian, German, and English. There were three versions of this text (1771, in two volumes; 1786, with the addition of a third volume; and 1799).

A precious copy preserved in its contemporary uniform bindings.