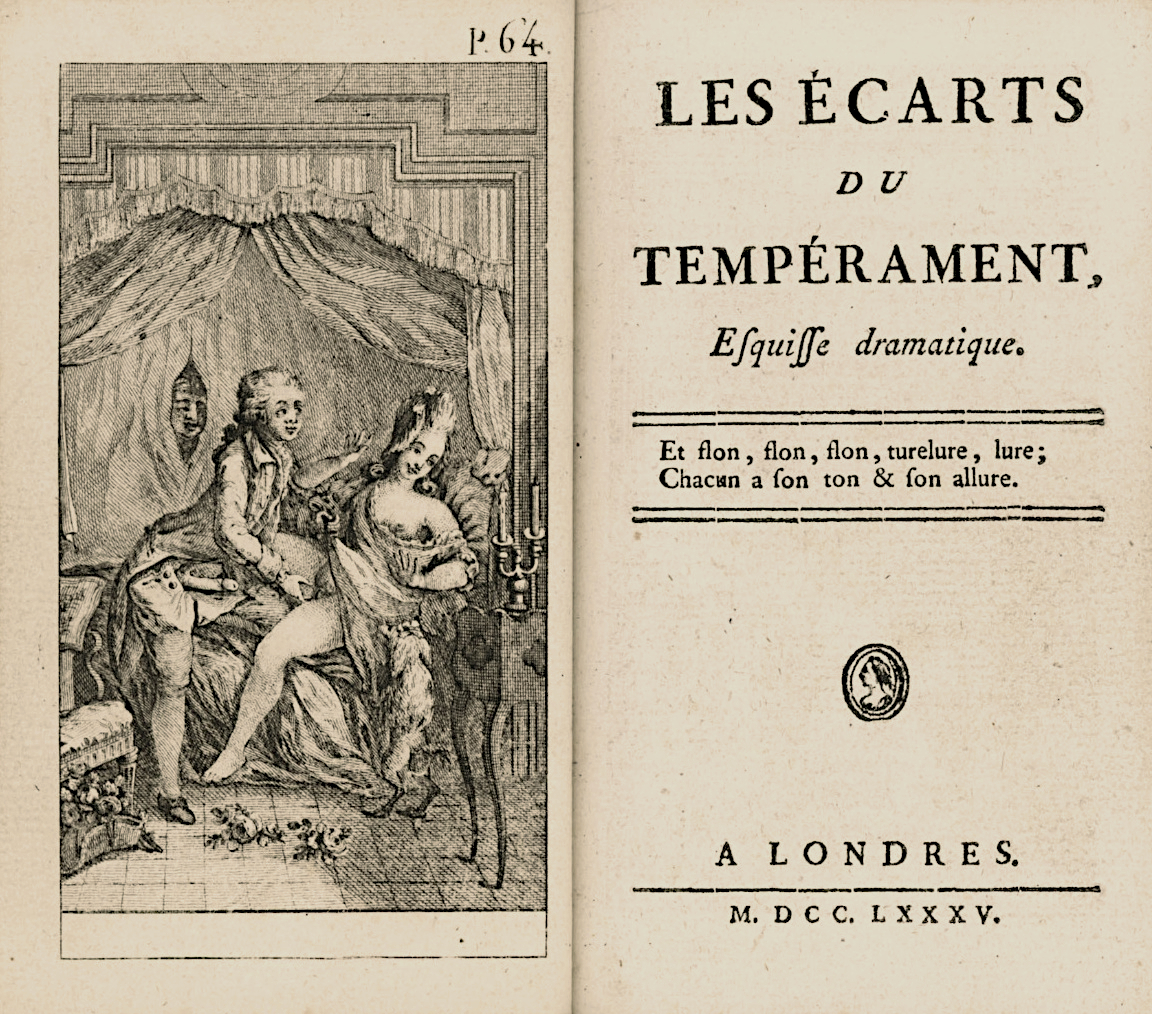

Londres, 1785.

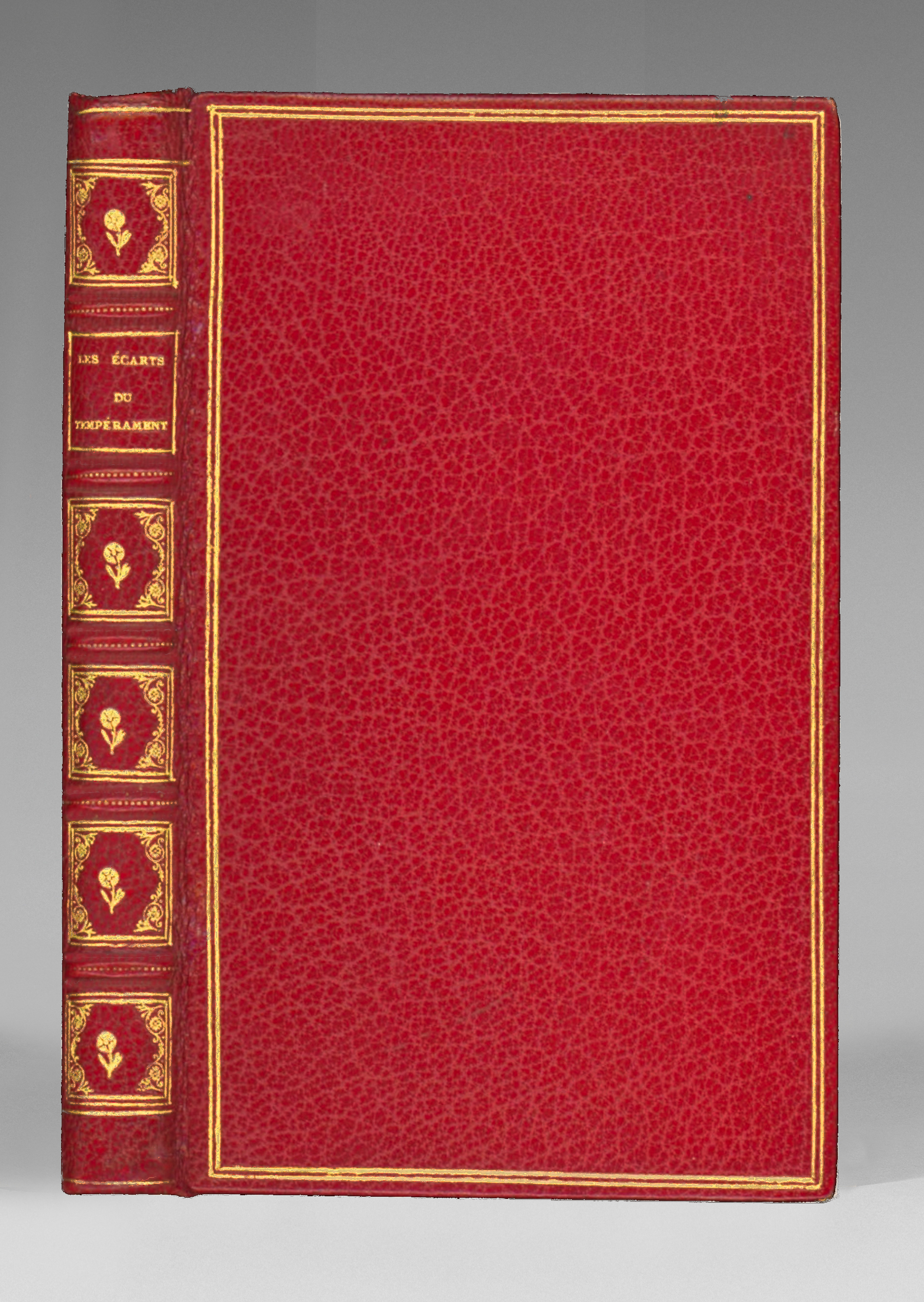

12mo, red morocco, double gilt fillet, spine decorated, gilt inner border, gilt edges. Binding from the end of the nineteenth century.

131 x 80 mm.

The “now unobtainable” first edition of the first publication of “Le Diable au corps”, printed as early as 1785, one of the most illustrious erotic novels to appear simultaneously with the works of the Marquis de Sade. Raymond Radiguet (1903-1923) will use this title for his autobiographical novel, published the year of his death.

Le Diable au corps is a picture of Parisian mores shortly before the Revolution, and Nerciat has complemented it with another: Les Aphrodites, which takes place some fifteen years later, during the first revolutionary convulsions. It was undoubtedly in connection with Le Diable au corps and Les Aphrodites that Baudelaire wrote the note he intended to expand on, “La Révolution a été faite par des voluptueux” (“The Revolution was made by voluptuous people”).

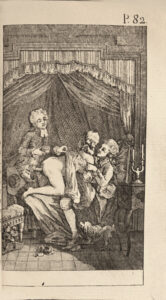

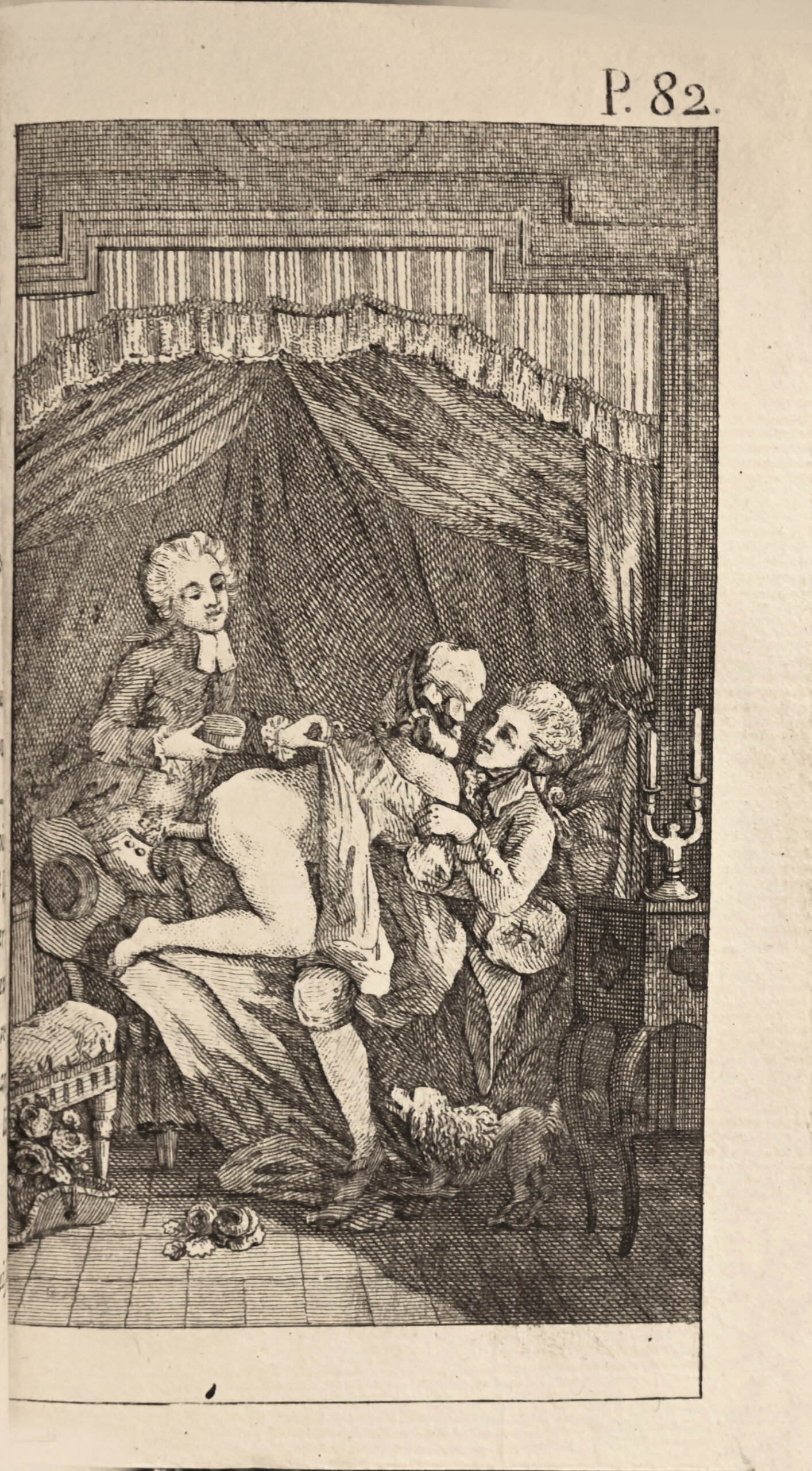

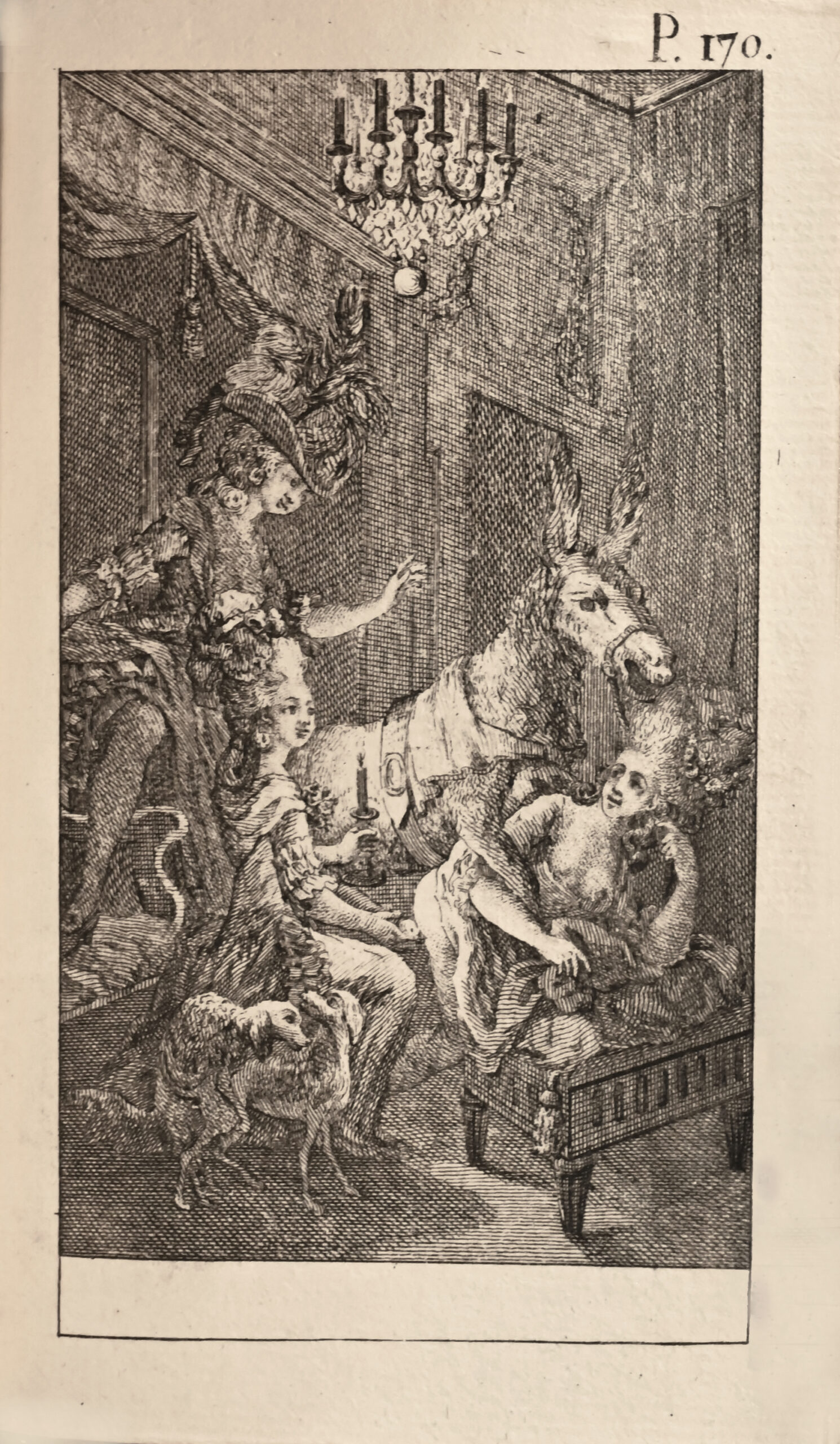

This extremely rare first edition features 4 erotic figures.

Published clandestinely in 1785, without the author’s consent, this edition provides the public with the first version of the first part of Le Diable au corps (1803), the text of which was still being written by Nerciat at the time.

This very free narrative takes the form of a crisply-worded, erotic dialogue between several characters: a superb marquise, the Comtesse de Motte-en-feu, a true piquant uglyron and fiery blonde who bears an unequivocal certificate of the most numerous & hottest adventures, a soubrette, a prelate, and so on.

Le Diable au corps was condemned to destruction by the Seine Assize Court on August 9, 1842, and by the 6th Chamber of the Seine Correctional Court on May 12, 1865.

Nerciat may not have been as politically astute or lucky as one of his illustrious patrons, Talleyrand, but he left posterity a literary work that is far less perishable.

His novels, so reasonable and appropriate in political philosophy, are brimming with joie de vivre and happy health, in stark contrast to the cynicism and harshness of the particularly corrupt and bloody political life of his time. If his work reflects his life, the Chevalier, a subtle libertine, must have known some very happy moments through so many professional vicissitudes. If it doesn’t reflect his life at all, this chaotic life must have been particularly painful for him to extract such imaginary compensation from himself. If a decision has to be made, his work is largely autobiographical, and offers a very faithful mirror of the free-spirited mores (but without their corruption and violence) of the French aristocracy, which the reaction of the post-Napoleonic Restoration had not yet overshadowed with its implacable repression of morals. In short, his life was as dangerous as his work is joyous.

“André de Nerciat would have written Le Diable au Corps a few years before the Revolution, and would have had it printed as early as 1789 or 1790, had events not caused his project to be postponed. He complained that, as early as 1785, he had fallen victim to a counterfeiter who, even before the work had been completed, had published part of it, introducing many errors and making disastrous alterations here and there: “Not the slightest deviation, not the slightest addition, the slightest retrenchment that is not a counter-sense, a platitude, or at least a fault against taste, not to mention the innumerable purely typographical deformities“. The title of this forgery, or rather pre-forgetting, which cannot be found today, was: les Écarts du tempérament ou le Catéchisme de Figaro, esquisses dramatiques. London, 1785, 18mo, with the epigraph:

Et flon flon, lure lure lure,

Chacun à son ton et son allure,

It was reprinted a few years later under a different title: les Écarts du libertinage et du tempérament ou Vie licentieuse de la comtesse de Motte-en-feu, du Vicomte de Molengin, du valet Pinefort, de la Conbanal, d’un âne et de plusieurs autres personnages. Nouvelle édition. A Conculix, chez l’abbé Boujarron, bon bretteur, 1793, 18mo of 132 pages with engravings.

It is unlikely that the first of these two editions of part of the future Diable au corps was actually published without the author’s complicity. It is certainly possible that it was printed without Nerciat’s proofreading and signature on the final proofs, but it goes without saying that the publisher had a manuscript that could only have been circulated by Nerciat himself. Nerciat’s protests resemble the complaints of a prostitute whose modesty has been offended”. Pascal Pia, Les livres de l’enfer.