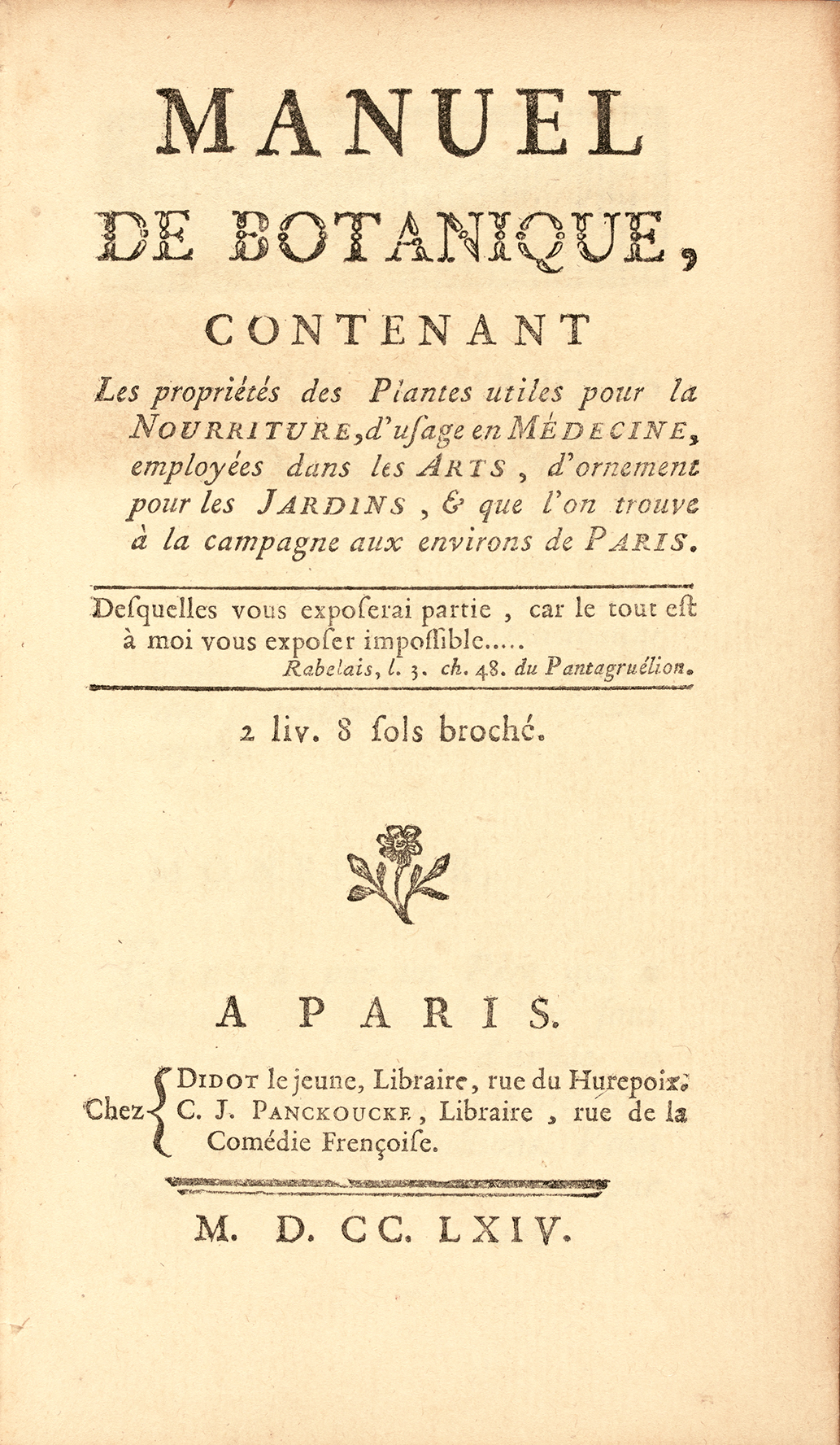

Paris, chez Didot le jeune, C. J. Panckoucke, 1764.

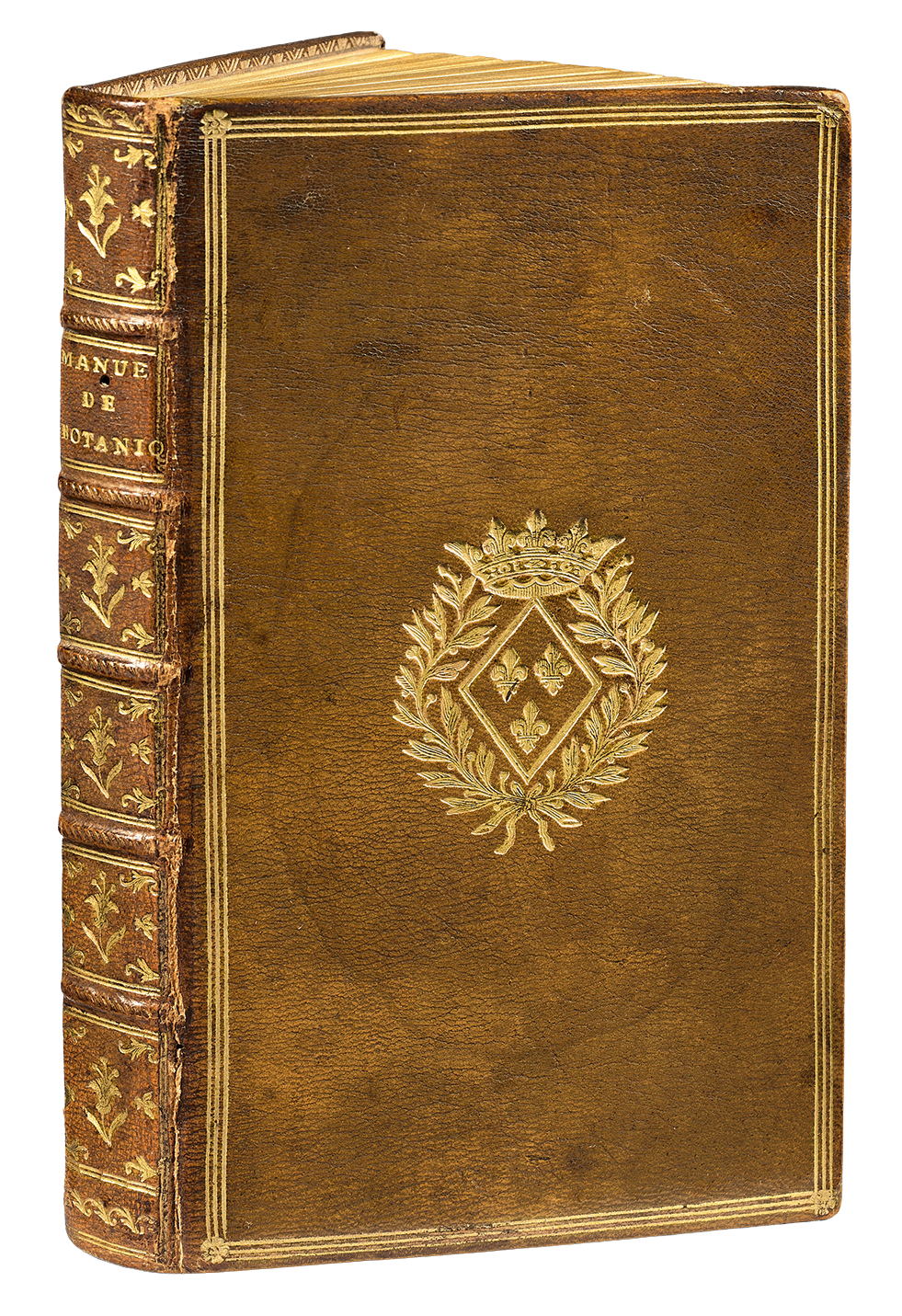

12mo of xxiv pp., 44 pp., 76 pp., 92, 94, (2), 75, (1) p. Full olive-green morocco, triple gilt fillet around the covers, arms stamped in the center, spine with raised bands and gilt decoration, gilt fillet on edges, gilt-rolled inner border. Contemporary armorial binding.

161 x 93 mm.

First edition of this manual of botany of the greatest rarity.

“The author has arranged the plants of which he speaks into four principal classes. The first includes those of which we eat various parts, differently prepared, either out of necessity or for pleasure, and those which provide us with agreeable drinks: they may generally be called plants useful for food; they are gathered in the first part and presented in the order of 58 families, established by B. de Jussieu. This part includes not only the plants commonly cultivated but also wild plants that can serve as food for the poor and during times of famine. To these are added those which Linné included among the edible plants of Sweden. The second class concerns plants used in medicine: only those approved in the pharmacopeia of the Faculty of Medicine of Paris have been admitted. The third is composed of plants employed in the arts. Finally, the fourth includes the plants whose property is to adorn places intended for promenades, that is to say, plants for the ornamentation of gardens; they are gathered here, with a short description of what gives them their merit, an indication of the season when they are enjoyed, and the place they can occupy in flowerbeds, lawns, water features, large and small groves, avenues, and other parts of a garden or a formal park. This manual concludes with very extensive latin and french tables: these tables contain the families, genera, and species of the plants mentioned in the work. Added is the Index or alphabetical table of genera under which the plants are placed in Vaillant’s Botanicon Parisiensis. Finally, one also finds the names of the families introduced by Jussieu. This work, considered from several aspects, is truly original; it seems designed for that class of citizens who wish to acquire from botany only the most pleasant and generally useful knowledge.” (Bibliothèque littéraire historique et critique de la médecine ancienne et moderne, II, p. 502).

“Both one group and the other will find satisfaction in this Manual. It also has the advantage of presenting an order of families based on the observations of the greatest of our masters. Finally, one will note that all our Plants have French names, which was lacking in almost all Catalogues. This kind of introduction to botany sheds great light on this science. One is led to believe that there is no plant without its particular usefulness. Only a very small number have their properties known; it is these plants that M. Duchesne discusses, limiting himself to those found in the countryside around Paris.

Apart from his knowledge, M. Duchesne has the merit of frankness. He takes pleasure in gratefully naming the various people who helped him with his work and shared their insights with him […] this work can only deserve the public’s approval and please all readers.” (L’Année littéraire, 1764).

Superb copy bound in contemporary olive morocco for M0adame Victoire, daughter of King Louis XV.

The Mesdames de France, Adélaïde, Sophie, and Victoire, each had their own library bearing the arms of France, but the books of Madame Victoire were bound in olive-green morocco.

“Madame Victoire was beautiful and very gracious. Her manner, her gaze, her smile were in harmony with the kindness of her soul. She lived with the greatest simplicity. Without leaving Versailles, without sacrificing the comforts of life or the soft spring armchair she never parted from and which, she said, would be her downfall, she forgot none of her duties, gave to the poor all that she possessed, and made herself adored by everyone. It is said that she was not indifferent to good food, but she redeemed these sins of laziness and gluttony by an ever-even temper and an inexhaustible benevolence.” (Quentin-Bauchart, Les Femmes bibliophiles de France, pp. 123-130).