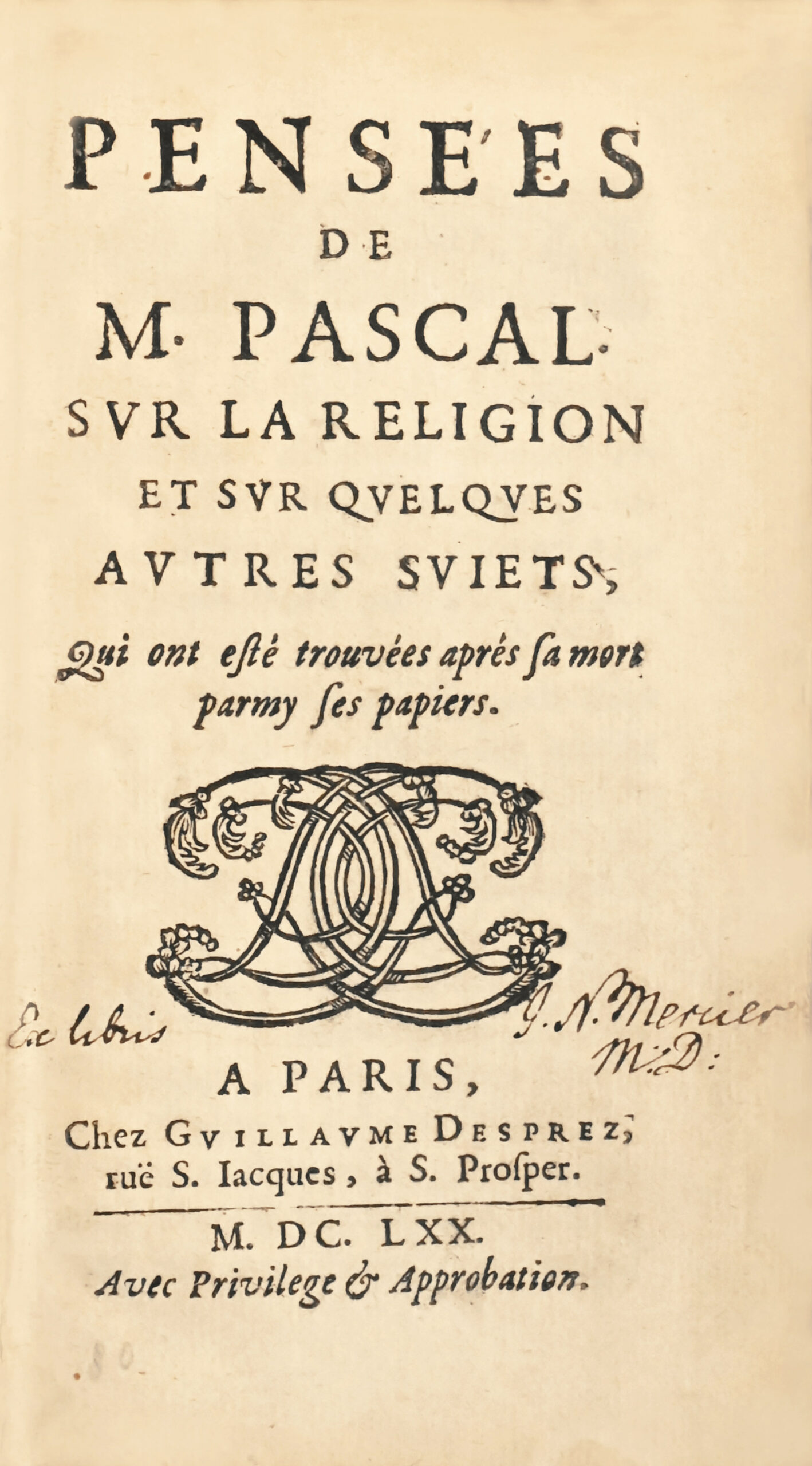

Paris, Guillaume Desprez, 1670.

12mo. Collation: 41 preliminary leaves, 365 pages, 10 leaves of table.

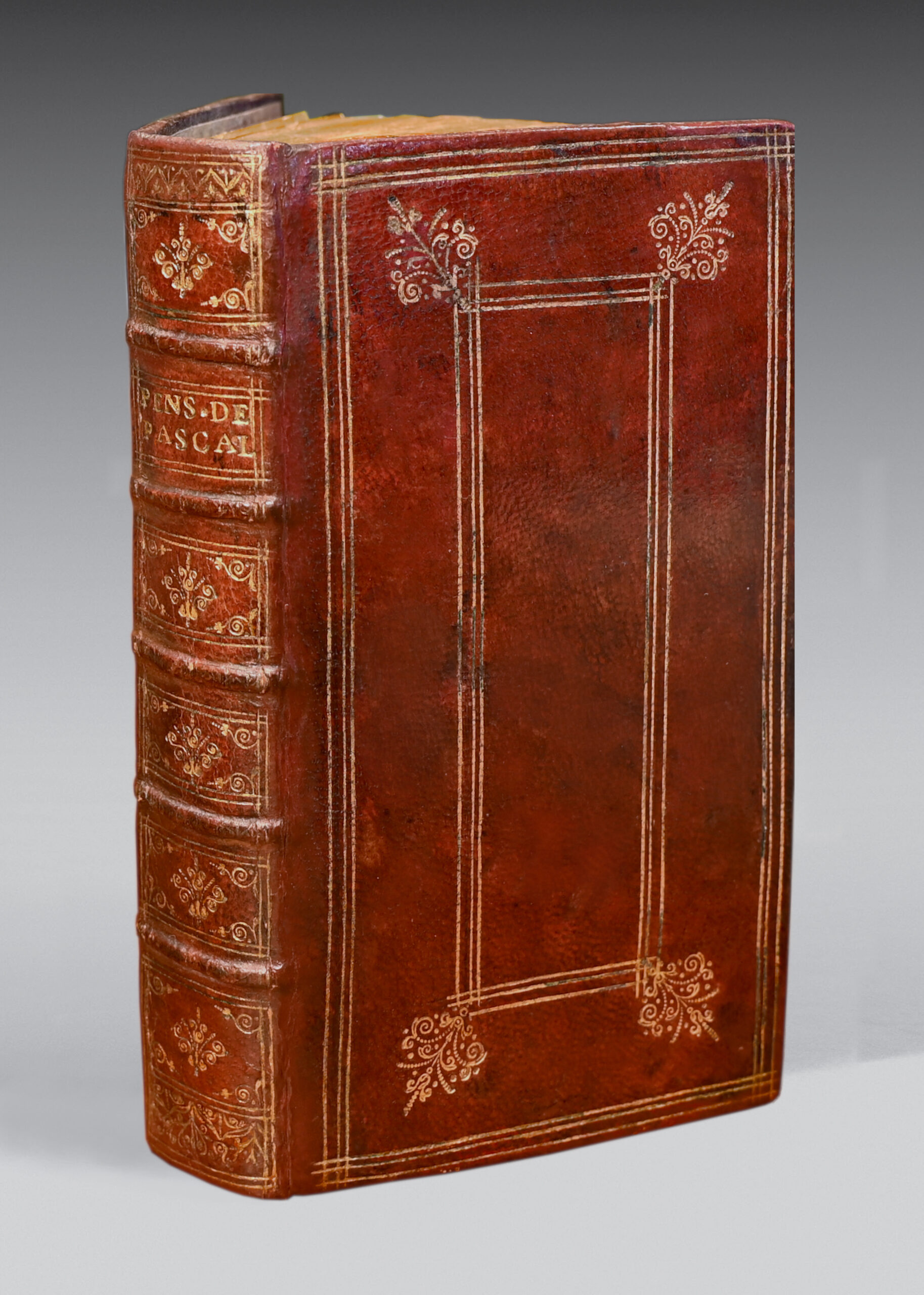

Full red morocco, panelled covers in the style of Duseuil, spine with raised bands richly decorated, gilt edges. Contemporary morocco binding.

148 x 82 mm.

Precious edition of the Pensées printed in the year 1670, bound in red morocco of the period, the copy of the Abbé de Saint-André, master at the famous Collège du Plessis-Sorbonne in the year 1698.

Copy belonging to the second of the four editions published in 1670 (Brunet, supplément II 167, gives it priority and calls it the original edition; Tchemerzine ranks it second, calling it the first counterfeit), from the library of the Abbé de Saint-André, master at the Collège du Plessis-Sorbonne, “A Paris, the year 1698, this day March 21”.

This college was founded in 1317 by Geoffroy du Plessis-Balisson, apostolic notary and secretary to Philippe le Long, under the name Collège Saint-Martin-au-Mont. But it quickly came to be known as the Collège du Plessis. It was joined to the Sorbonne in 1646 and then took the name Plessis-Sorbonne. Its buildings are now occupied by the current Lycée Louis-le-Grand.

The classical 19th-century bibliographers considered the present edition as the true original. Thus Deschamps in the Supplément de Brunet (II-167) described it as:

“Original edition; it consists of 41 preliminary leaves, 365 pages, and 10 leaves of table; the privilege (granted to sieur Périer), given in Paris on December 27, 1666, says at the end: Completed printing for the first time, January 2, 1670; there is an errata on the verso.”

- Petier was the first to carefully compare this edition with the unique copy of the 1669 edition, preserved in the Bibliothèque Nationale; the two editions are essentially the same; the number of pages, the ornaments, and the typographic layout are identical; the differences are these: the title is not exactly the same; the 1669 copy lacks ecclesiastical approvals, the privilege, and the table ends at the word Charnel, meaning the last nine leaves are missing; moreover, the 1669 copy was not revised — that is, it did not undergo the deletions or changes likely demanded by the Archbishop of Paris.

Two other editions appeared in the same year, 1670.

1/ “A second counterfeit under the same date, with identical collation, has a slightly different title. The monogram of G. Desprez is replaced by the fleuron from the Provinciales, quarto edition of 1657” (Tchémerzine, V, 71).

2/ The true second edition of the Pensées, this time with the errors corrected. The title is identical to that of the original edition but the collation differs: duodecimo of (39) leaves, 358 pages numbered as 334 and (10) leaves.

Among these four editions published in 1670, ours would occupy the second place in chronological order. It is extremely rare bound in morocco of the period.

“Pascal remains unique, not so much because he is ‘one of the greatest intellects to have appeared’ (Paul Valéry), but for his passion, his momentum, for that aggressiveness which seizes the reader’s soul, for those discoveries, those surprises, which he holds in store, which astonish and confound the reader and make him discover within himself not only abysses, but the means—or rather the only means—of crossing them.”

“As it was known that Pascal had planned to work on religion, great care was taken after his death to collect all the writings he had made on that subject. They were found all together, strung together in various bundles, but without any order, without any sequence… And all of it was so imperfect, and so poorly written, that it took immense effort to decipher them,” says Étienne Périer in his preface. Pascal’s friends, Roannez, Brienne, and Étienne Périer, ultimately decided to publish the fragments, arranging them in a certain order, grouping together the thoughts with related subjects, merely “clarifying and embellishing” them. The result of this work was the 1670 edition.

Copies of Pascal’s Pensées printed in 1670 and bound in contemporary morocco are rare; one belonging to the first original edition of 1670 was sold for €230,000 by Sotheby’s 24 years ago (Sotheby’s, December 5, 2001); another, from the Pierre Bérès collection, trimmed and restored, was sold for €120,000 twenty years ago.

Precious copy bound in decorated morocco of the period with superb provenance: “Labbé de St André – Collège du Plessis-Sorbonne – ce 21 mars 1698”

The rise of Paris as the capital of France was supported by the development and influence of the University of Paris. It came into being during the 12th century as a result of the steady growth of the Parisian schools grouped on the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève. These schools provided an education preparing for three degrees: the baccalaureate (grammar, dialectic, rhetoric), the license (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, music), and the doctorate (medicine, canon law, theology).

By the end of the Middle Ages, the University of Paris had become the largest cultural and scientific center in Europe, attracting some 20,000 students. Its reputation rested on the prestige of its teachers, but also on its libraries, whose richness was matched only by the papal library. The University of Paris was the cradle of the “second French humanism” in the 15th century, and it was at the Sorbonne that the first printing press in France was installed in 1469 by the royal librarian Guillaume Fichet and the prior of the college, Jean Heynlin.

“The institution, endowed with a significant library, a chapel, and dormitories intended for the comfort of its students, was indeed associated with the faculty of theology, and established itself permanently in the heart of medieval Paris. From century to century, the college later known as ‘la Sorbonne’ played an increasingly important role in the life of the Kingdom of France, actively participated in intellectual debate, and tirelessly pursued its educational mission. In 1622, its illustrious principal and soon-to-be cardinal Richelieu, seeking a place to house his own tomb, undertook major renovations and began the construction of a chapel. This marked the beginning of a continuous modernization of the buildings, as the University’s reputation kept growing throughout Europe. In 1698, the Abbé de Saint-André, master at the Collège du Plessis-Sorbonne, inscribed his handwritten ex-libris on this copy of the 1670 Pensées bound in morocco of the period.