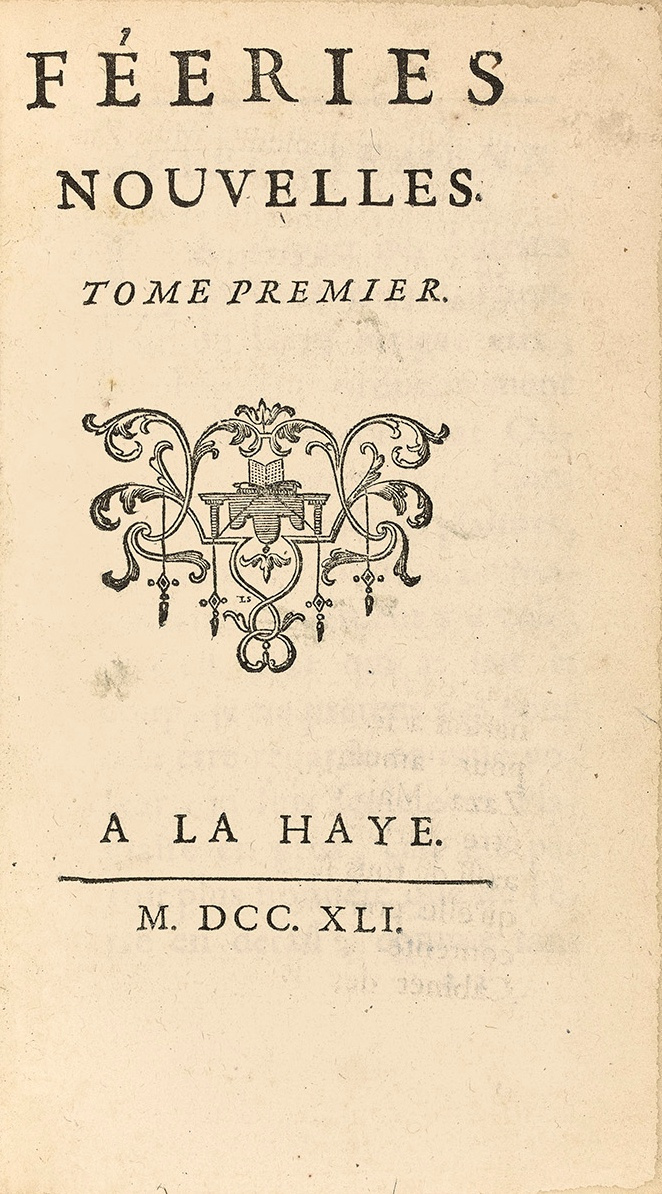

A La Haye, 1741.

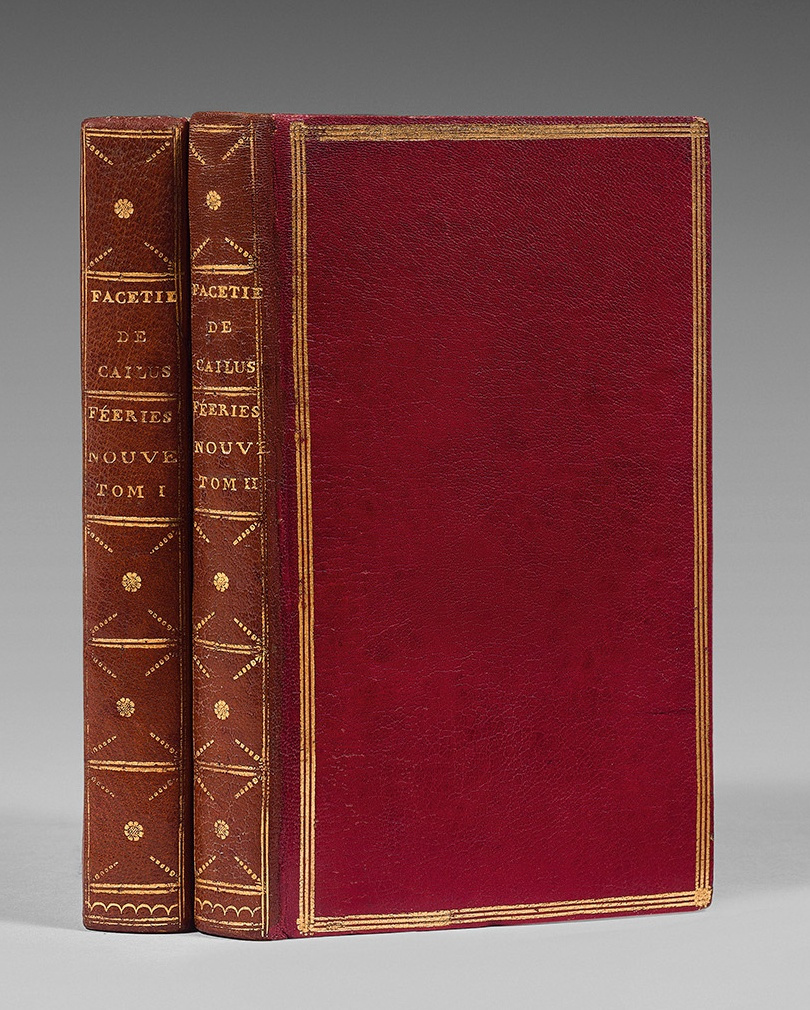

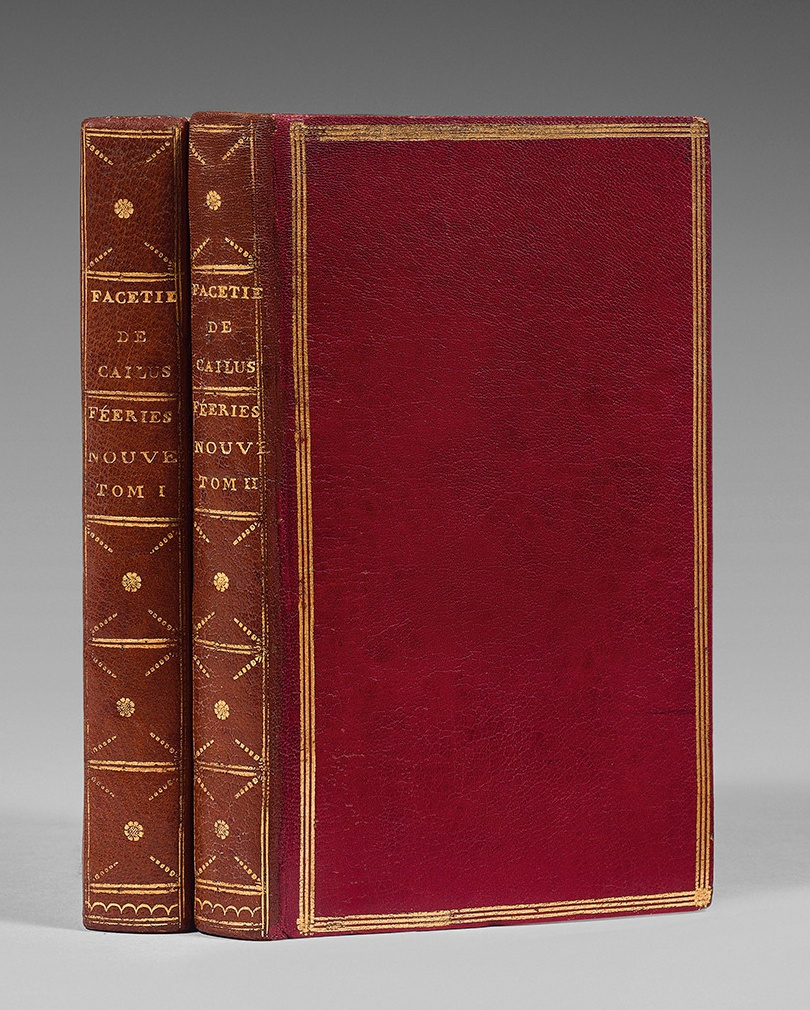

2 parts in 2 volumes 12mo [158 x 90 mm] of: (3) ll., 346 pp; (1) l., 390 pp., (1) table leaf. Red morocco, triple gilt fillet around the covers, decorated flat spines, gilt edges. Eighteenth century binding.

First edition of fourteen delightful fairy tales, exceedingly rare in ancient morocco: «Le Prince Courtebotte et la princesse Zibeline ; Rosanie; Le Prince Muguet et la princesse Zaza ; Tourlou et Rirette ; La princesse Pimprenelle et le prince Romarin ; Les Dons ; Nonchalante & Papillon ; Le Palais des Idées ; Lumineuse ; Bleuette & Coquelicot ; Mignonnette; L’Enchantement impossible ; Minutie ; Hermine. »

Their reprinting in the Cabinet des fées was met with reservations by the publisher, who considered them a little too licentious.

(Les Contes de fées, B.n.F., 2001, n° 32 ; Gumuchian, n° 1519: “Rare first edition.”).

Barchilon (Le conte merveilleux français, 1690-1790, pp. 125-128) – who praises Caylus and his tales – has shown that Le Prince Courtebotte could have been one of Andersen’s sources for The Snow Queen.

“Caylus is the friend of modern writers, he is the mentor of the famous diners du-bout-du-banc at Mlle Quinault’s; a society where free thought and a taste for pleasure bring together writers like Crébillon fils, Voisenon, Moncrif, Duclos and sometimes Maurepas or Montesquieu. It was here that the “Académie de ces dames et de ces Messieurs” and the “Académie des colporteurs” were born, collective producers of facetious and satirical works; it was also here that, in a sort of writing workshop before the letter, all sorts of short works in all genres were produced, of which we still have, for example, the collection of the Étrennes de la Saint-Jean, certain texts attributed to Crébillon, or even Rousseau’s Reine Fantasque. The genre poissard, which one liked to practice after Vadé, found in Caylus an amateur as well as a collector, who ended up writing a whole novel in this style in 1740: Histoire de Guillaume (1740), not to mention numerous parades. These acquaintances and friendships did not, however, link the Count to the encyclopedist milieu, whose sectarianism he despised; this habitual guest of Mme Geoffrin liked neither Voltaire nor d’Alembert and hated Diderot.

With regard to Caylus’ fairy production, Julie Boch defends an original thesis: that of the coherence of an aesthetic which is actualized as much in the scholarly production of the Count as in the storytelling work. Translator of the famous Tyran le Blanc (1737), author of an essay: Sur l’origine de la chevalerie et des anciens romans (1756), this friend of the Count of Tressan must be counted as a figure to be re-evaluated in the cohort of “classical” and “modern” theorists of the romance genre (and its marvelous component), in the company of Chapelain, Huet, Perrault, Addison, and so on, but also some relatively interesting opponents of the genre on moralizing grounds, from the abbé de Villiers to Moncrif. Concerning the tale and the fairyland, Caylus is the author of two memoirs produced within the framework of the Académie des Inscriptions, one Sur les fabliaux (1753), the other Sur la féerie des anciens comparée à celle des modernes (1756): “these two theoretical essays, written subsequently to three of the four collections of tales,” writes Julie Boch, “shed light in retrospect on Caylus’s conception of the genre he practised, which was both historical and aesthetic. There is a return to the aesthetic of the ‘clear line’ exemplified by Perrault: elegance, naivity, briefness, simplicity; but above all a refocusing on the axiological dimension which opposes Caylus to the satirical and libertine trend which has prevailed since 1730.

Caylus works on the tale in a broad perspective, as an element of the muthos (apologues, various fabulous tales, biblical parables); he places the marvelous tale in the filiation of the medieval novel, lays down milestones for the transmission of certain elements from Antiquity, and goes back to India (would he be one of the first bearers of the Indianist theory? ); unlike Huet, he insists on the continuity of a transmission from the Arabic culture to La Fontaine. Julie Boch clearly shows how this thought is reflected in fiction in some of his tales. She also shows the precision of his culture in relation to the modern history of the genre, particularly in relation to the great storytellers of the seventeenth century, whom he quotes or from whom he takes onomastic or situations. She confirms, after J. Barchilon and R. Robert, that “Caylus’s literary enterprise is presented doubly as a return to the roots”, underlining what he shares with the educational tale in the manner of Fénelon.

The part devoted to the new fairylands concerns Caylus’ double game between “convention and parody” in his fairytales. Julie Boch pinpoints formulas and procedures, props and magical metamorphoses, etiological tales and tales with challenge, contrasts and more or less sophisticated parallels, to show that Caylus attempts to finely renew the genre. As for its form of parody, it uses the supposed skills of amateurs to cut short, to create burlesque, to inscribe a clear intertextuality, to demystify kings and fairies, the former being the victims of a satirical intention that clearly indicates the period in which these tales were written. As for the edition of the texts themselves, the relevance and quality of the literary annotation must be emphasised: quotational or intertextual relationships with earlier storytellers (Aulnoy, Lhéritier, Murat, de la Force, Lintot), with Perrault, Fénelon, Galland, Bignon, Hamilton, Crébillon, the Montesquieu des Troglodytes (La Belle Hermine et le Prince Colibri), with the Baroque novel, the Arthurian novel and the Amadis, lounge poetry, the world of pastoral, the classical moralists, etc. , or even the folkloric filiation through certain standard tales. In this way, we can see how much the author’s tale of wonder gains from being read as a literary text from one side to the other.

In Caylus’s Fairy tales, the following stand out at the moral level: political criticism (relatively limited but fierce towards kings or tax collectors), satire of values (very pronounced, in the tradition of La Bruyère and Montesquieu), rejection of values related to materialism and libertinism as well as a certain “bourgeois” approach to the world; moral construction of characters tested by experience, in a context where the fairy staff loses its omnipotence in favour of a greater humanity. Aesthetically: return to the classical idea of natural, rejection of baroque elements such as: « tout le fracas devenu si commun dans les histoires de féerie » (Rosanie), a reevaluation of the pastoral genre, but also a “contamination of the fairy genre by a realist aesthetic” that Julie Boch links, according to her thesis of the coherence of the whole Caylusian project, to the taste for tangible details, ordinary uses, and local colour characteristic of the scholar and the art lover.

A very attractive and exceedingly rare copy of the original edition bound in elegant antique morocco.

From Cécile Eluard’s library.