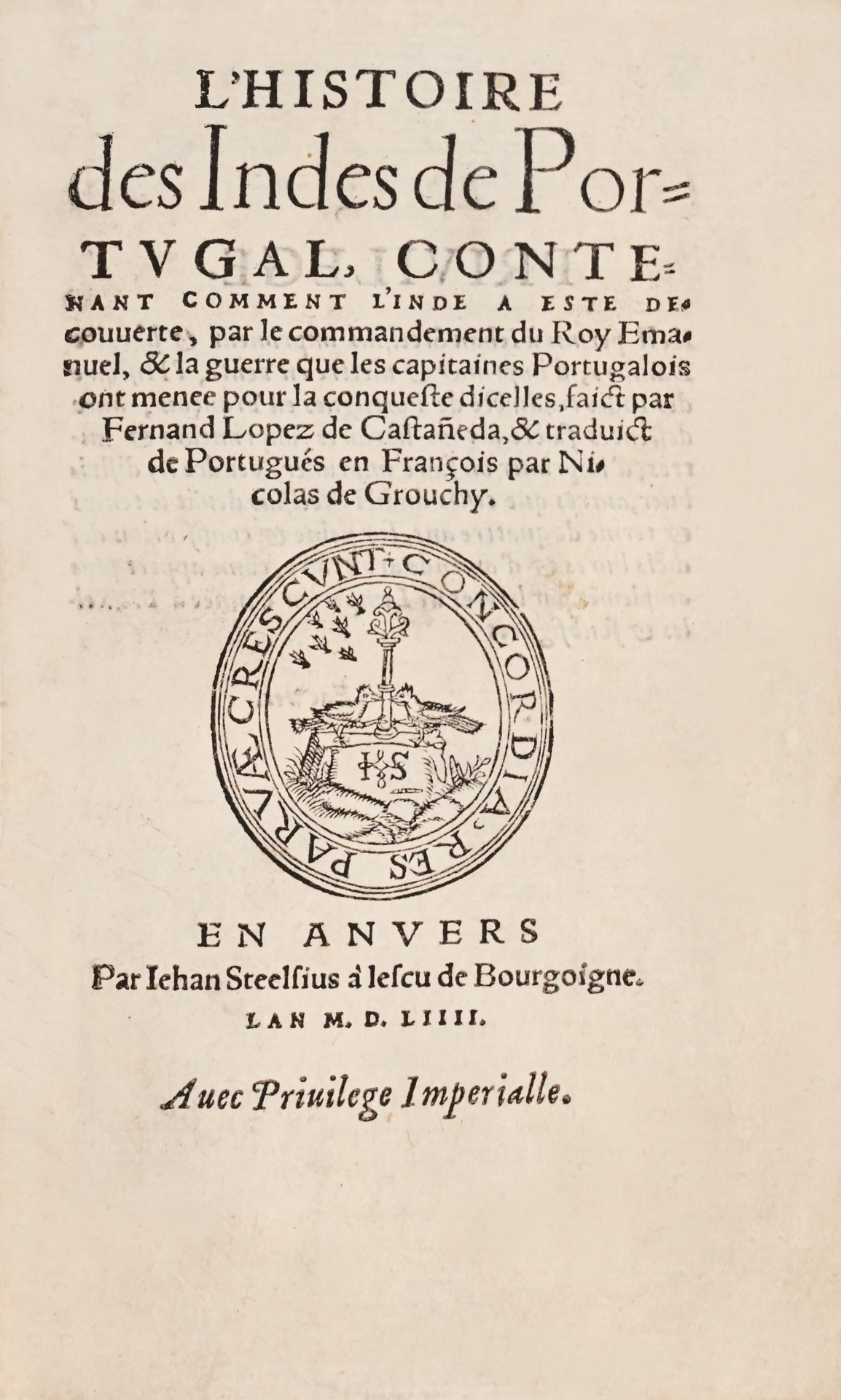

Antwerp, Jehan Steelsius à l’escu de Bourgogne, 1554.

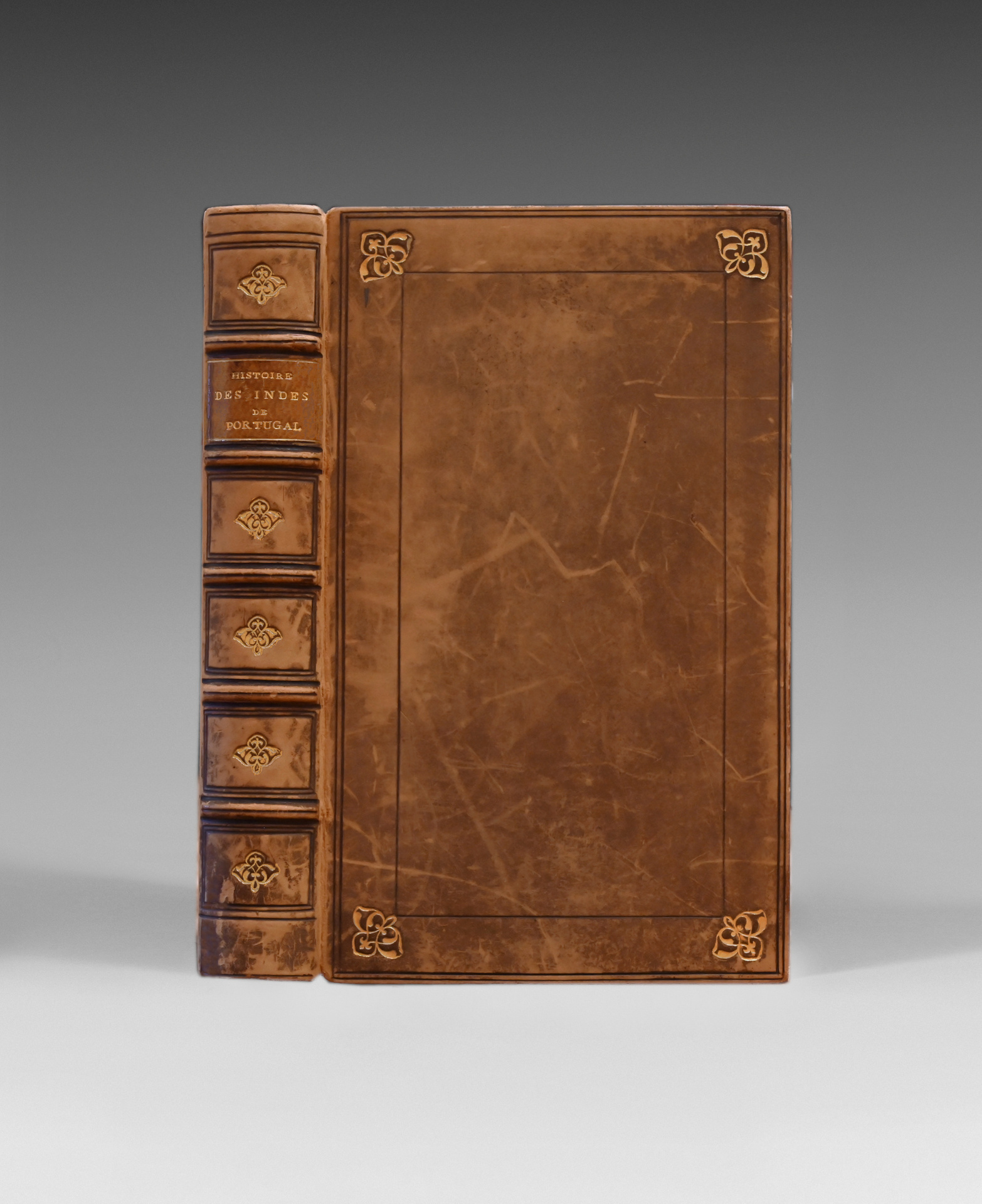

Small 8vo [151 x 92 mm] of (4) ll., 211 ll. Light-brown calf, double blind-stamped fillet around the covers with corner fleurons, spine ribbed and decorated in the same manner, gilt edges, inner gilt border. Petit successor of Simier.

Second edition of the French translation by Nicolas de Grouchy, published only one year after the one given by Michel de Vascosan.

Borba de Moraes, I, p. 142 ; Sabin n°11388. Not in the John Carter Brown Library Catalogue.

This volume contains the first book of Lopes de Castanheda in which the author gives an account of the voyage of Pedro Alvarez Cabral in India in 1500, in the course of which Brazil was discovered.

This first book comprises the account of Cabral’s discovery of Brazil.

It is worthy of note that the English translation of this first book by Nicholas Lichfield was not published in London till 1582.

Pedro Alvarez Cabral was a Portuguese navigator born around 1467 in Belmonte (Portugal), who died probably around 1520, perhaps in Santarem (Portugal). The son of Fernão Cabral and Isabel de Gouveia, Pedro Álvares Cabral was born into a noble family with a long tradition of service to the Portuguese crown. The young man was highly regarded by King Manuel I. Cabral was appointed admiral and took command of a squadron of 13 caravels that left Lisbon in March 1500 for the Indies. His aim was to follow the route opened by Vasco da Gama in 1497 in order to consolidate the commercial links established in the East and to continue the conquest of new territories begun by his predecessor.

Cabral followed Vasco da Gama’s instructions to the letter and headed southwest to take advantage of the trade winds. Favourable winds carried Cabral so far west that on 22 April 1500 he discovered what he thought was an island and named it Land of the True Cross (Vera Cruz). Renamed Santa Cruz (Land of the Holy Cross) by the king, the territory eventually took on its present name, Brazil, in reference to the brasil wood, an “ember-coloured” dyewood found in abundance.

According to reports, Cabral tried to be affable with the natives, whom he received on board his caravel. Nevertheless, he took possession of the new lands, which were rightfully Portugal’s according to the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), and sent one of his ships back to Portugal to inform the king. From then on, maps of the region showed a vast expanse of land with ill-defined borders under Portuguese rule, and where ships from Europe stopped off to reach the Cape of Good Hope and the Indian Ocean.

Cabral stayed in Brazil for only a few days before setting sail for the Indies, but the second part of his journey was marked by a series of unfortunate events. On 29 May, as the fleet rounded the Cape of Good Hope, four caravels disappeared. Several men died in the wreck, including Bartolomeu Dias, the Portuguese navigator who discovered the Cape in 1488. The rest of the fleet reached India and dropped anchor in the port of Calicut on 13 September 1500. The zamorin (local chief) welcomed them and allowed them to establish a fortified trading post. Disputes soon broke out with the Arab merchants, however, and the trading post was attacked on 17 December by a large armed force. Most of the Portuguese defenders were killed before reinforcements could arrive.

Cabral retaliated by bombarding the city and capturing ten Moorish vessels, whose crew he executed. He then headed south to the port of Cochin, where the local chiefs gave him a warm welcome and allowed him to trade in the precious spices, which he loaded onto the six caravels he had left. After two more stopovers on the same coastline to complete his load, Cabral set off on his return journey on 16 January 1501. He lost two more caravels on the way and finally reached the mouth of the Tagus on 23 June 1501 at the head of four ships.

“The expedition remained on the coast eight days. The General ordered a high stone cross to be erected here, and named the country. ‘ La Tierra de Santa Cruz,’ or the Land of the Holy Cross, which name will be found on the earliest maps of the Eastern portion of the continent of South America. From here Cabral sent home a caravel, with letters to the King, giving an account of his voyage hitherto, and stating that he had left two exiles here to examine the country; and particularly to ascertain if it were a continent, as it appeared to be from the length of the coast he had passed. He likewise sent one of the natives to show what kind of people inhabited the country.” Bartlett, Vol. I, pp. 263-4.

« ‘Historia de descobrimento e conquista da india por los Portogueses, por Fernando Lopez de Castaneda. Coïmbre, 1552-1554, 8 folio volumes.

This work was entirely translated into Italian under the following title: ‘Istoria dell’Indie orientali, scoperte e conquistate de Portughesi… Venise, 1578, 2 volumes 4to.

This work is very rare and much sought-after, because it is the most complete history of the conquest of the Indies by the Portuguese.

Only a part of this history was reprinted in Antwerp in 1554.

The first book only was translated into French under the following title: ‘Le Premier livre de l’Histoire de l’Inde, contenant comment l’Inde a été découverte par le commandement du roi Emmanuel’… Paris, 1553, 4to.” (Bibliothèque universelle des voyages, 1808).

’Montaigne read the work of Castaneda ‘Histoire de la découverte et de la conquête des Indes par les Portugais’. We already know that his library contained a translation into Castilian of the first of the eight books of Castaneda; but he couldn’t read Spanish. That is probably from the French compendium edited by Goulard that Montaigne could get to know the history of Castaneda…

Here are three abstracts that seem to derive from it:

Montaigne

Et au quartier par où les Portugais escornerent les Indes, ils trouverent des estats avec cette loy universelle et inviolable, que tout ennemy vaincu par le roy en presence ou par son lieutenant est hors de composition de rançon et de mercy.

(I, 16, t. I, p. 94)

En une nation, le soldat qui, en un ou divers combats, est arrivé à présenter à son roy sept testes d’ennemis est faict noble.

(I, 23, t. 1, p. 158).

Castaneda

Cachil disoit la coustume inviolable estre qu’en toutes les batailles esquelles les Roys ou leurs lieutenans se trouvoyent, on faisoit mourir sans aucune remission tous les ennemis qui avoyent attendu le combat ou l’assaut.

(L. 14, ch. 15, f. 416).

Correa sçeut que quiconque en ces isles peut porter à son Roy à diverses fois sept testes d’ennemis tuez en guerre, il est fait chevalier et gentil homme qu’ils appellent Mandarin ».

(L. 14, ch. 15, f. 416).

[…] Pour le Portugal, Montaigne s’appuie sur « le premier livre de la conquête des Indes par les Portugais », histoire écrite en espagnol par Lopez de Castaneda et dont nous avons vu Montaigne utiliser d’autres parties dans ses ‘Essais’ ». (P. Villey, Les Livres d’histoire moderne utilisés par Montaigne, 1972, p. 105).

A precious copy of this rare account of a journey to India and Brazil preserved in its binding signed by Simier’s successor Petit.