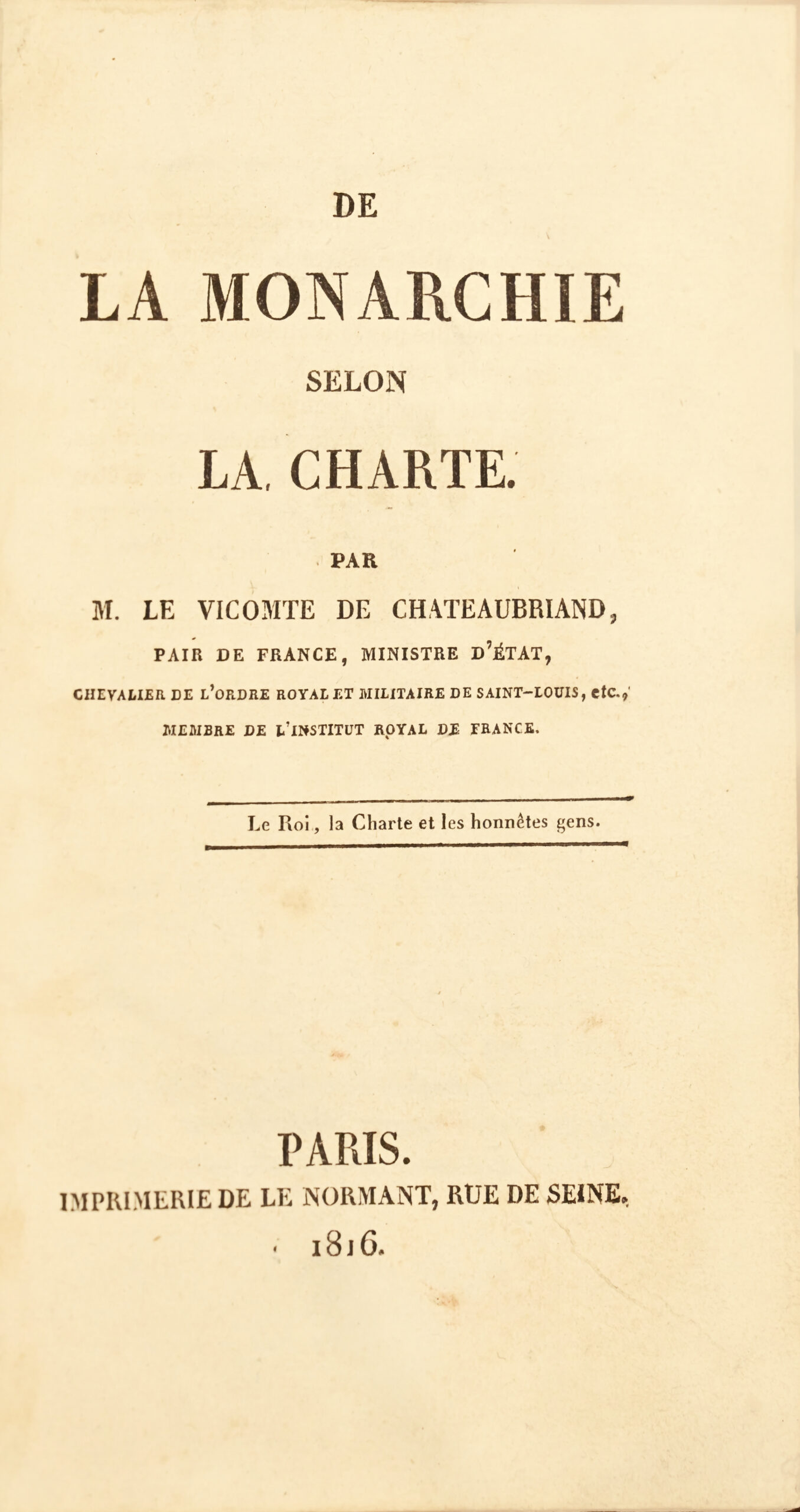

Paris, Le Normant, 1816.

8vo of vi pp., 304 pp. Small tear p. 19 without loss, pale waterstain at the top of few leaves.

– [Followed by :] Mémoires, lettres et pièces authentiques touchant la vie et la mort de S.A.R. Monseigneur Charles-Ferdinand-D’Artois, fils de France, Duc de Berry.

Paris, Le Normant, 1820.

(2) ll., ii pp., 1 full-page portrait, 299 pp. 3 browned leaves.

Green morocco, covers richly framed with double gilt fillets and borders, decorated flat spine, inner gilt border, pink tabis endleaves, gilt edges. Contemporary binding.

205 x 125 mm.

I/ Extremely rare first edition of this political pamphlet by Chateaubriand, which angered Louis XVIII and led to the author’s dismissal from his ministerial position.

The pamphlet was banned on September 18, 1816, and all copies seized and destroyed.

It is so rare that it escaped bibliographers such as Vicaire and Carteret.

With the printed title page containing the words “Ministre d’Etat” (Minister of State), later removed.

“All editions and issues of this pamphlet made by Le Normant uniformly bear the above title. They are all considered as first editions; they were seized by order of Décazes.” (Talvart, III, 10)

“Political work by François-René de Chateaubriand (1768-1848), published in 1816 and immediately banned by the Bourbon police. The author, who had shown his attachment to the cause of France’s ‘legitimate’ sovereigns, notably in his ‘De Buonaparte et des Bourbons’, could not – after the disappointments of the Restoration and especially the reactionary policies of the ultra-royalists – fail to show his rebellious spirit, by championing new social ideas; admittedly, he did so in a very personal way, letting himself be carried away by the impetuosity of his strongly egocentric vision of things. In this libel, he defended the constitutional charter, which had helped the liberals of France welcome Louis XVIII’s return and the start of his government. A return to the ancien régime was no longer possible. As minister, the author wants, in this publication, to tell ‘the truth to the king‘; for the Council of which he is a member does not, unfortunately, meet for the purpose of allowing its members to express their personal opinions on the nation’s most important issues. It is precisely because he intends to defend legitimacy, that he feels it his duty to affirm once again the need for the monarchy to be constitutional (return of parties, freedom of the press and other parliamentary prerogatives). The evils of despotism would, in fact, be worse than those of a liberalism which, guided in the right way – the English way – would bring new glory to king and country. The work, published a few days after the dissolution of the famous ‘Chambre introuvable’, aroused the indignation of Louis XVIII who, under the influence of his ultra supporters, simply dismissed the author from his ministerial position“. (Dictionnaire des Œuvres, IV, 603).

Three months after the publication of De Buonaparte et des Bourbons, in July 1814, his connections in the high aristocracy and the friendship of Madame de Duras had earned him an appointment as ambassador to Sweden, a post he never reached but for which he received a salary. In April 1815, the King allowed him to follow him to Ghent, and admitted him to the council “to speak from the inside”. On his return from Ghent, after the Hundred Days, he became Minister of State, an honorary but well-paid position that had been taken over from the Ancien Régime, and was part of the first batch of the Chamber of Peers. But Chateaubriand, who under the first Restoration had been close to the center and had eloquently and skillfully defended the Charter in his Réflexions politiques of October 1814, which had won him the favor of Louis XVIII, now moved closer to the ultra-right, which had just won the elections to the Chamber of Deputies. He became one of this party’s main spokesmen in the Chamber of Peers. He had been outraged by Fouché’s entry into the Ministry, and felt that the Hundred Days had demonstrated the need to rebuild French society on traditional foundations. As the King had decided to maintain a government of the center for reasons of both foreign and domestic policy, Chateaubriand soon found himself thrown into opposition to the Ministry and, in a muted way, to the sovereign. The break came in September 1816, when he published La monarchie selon la Charte (Monarchy according to the Charter), in which, despite the advice he had received from Louis XVIII, he criticized the Richelieu-Decazes ministry, which he felt was too indulgent of “revolutionary interests”, and the decision to dissolve the untraceable Chambre. In retaliation, he was stripped of his title of Minister of State, forcing him to sell his beloved Vallée-aux-Loups.

The work is a war machine against Decazes and his policies. The author denounces press censorship and attacks the Ministry of General Police. The work severely criticizes the three Ministries of the Restoration.

The work was a runaway success, provoking the anger of Louis XVIII and Decazes, who banned it and had the seized copies destroyed.

Chateaubriand was struck off the list of Ministers of State and lost his honorarium.

The Mémoires d’Outre-tombe include the letter Chateaubriand wrote to Count Decazes on September 18, 1816, when the latter learned that his work De la Monarchie selon la Charte had been seized on his orders. Here is an extract:

« Monsieur le comte,

J’ai été chez vous pour vous témoigner ma surprise. J’ai trouvé à midi chez M. Le Normant, mon libraire, des hommes qui m’ont dit être envoyés par vous pour saisir mon ouvrage intitulé : De la Monarchie selon la Charte.

Ne voyant pas d’ordre écrit, j’ai déclaré que je ne souffrirais pas l’enlèvement de ma propriété, à moins que des gens d’armes ne la saisissent de force. Des gens d’armes sont arrivés, et j’ai ordonné à mon libraire de laisser enlever l’ouvrage.

Cet acte de déférence à l’autorité, Monsieur le comte, n’a pas pu me laisser oublier ce que je devais à ma dignité de pair. Si j’avais pu n’apercevoir que mon intérêt personnel, je n’aurais fait aucune démarche ; mais les droits de la pensée étant compromis, j’ai dû protester, et j’ai l’honneur de vous adresser copie de ma protestation. Je réclame, à titre de justice, mon ouvrage ; et ma franchise doit ajouter que, si je ne l’obtiens pas, j’emploierai tous les moyens que les lois politiques et civiles mettent en mon pouvoir.

J’ai l’honneur d’être, etc.

Vte de Chateaubriand. »

II/ First edition of these famous and vibrant memoirs commissioned by the royal family from Chateaubriand as a tribute to the duke de Berry.

Talvart, III, 19; missing from Carteret and Vicaire.

This biography of the Duke de Berry, son of Charles X, appeared in the year of his assassination by Louvel just outside the Opéra, rue de Richelieu, on February 13, 1820. The father of two English daughters by a first marriage, he presented them to his wife, the Duchesse de Berry, on his deathbed.

Composed “from the most precious original documents” (Avertissement), these Memoirs include letters from Louis XVIII, Charles X, the duke d’Angoulême, the duke de Berry, the Prince de Condé, and a fragment of an unpublished diary.

The work received an inestimable reward. The Duchesse de Berry wanted the Mémoires to be buried with the heart of Louvel’s victim.

A precious copy preserved in an elegant, finely decorated contemporary binding in green morocco.